Overview

The Emergency Quota Act was part of a long winded effort by Congress to limit immigration into the United States during the early 1920s. This effort began in 1917 with a law requiring Immigrants pass a literacy exam (in a language of their choice) to enter and remain in the country. The President at the time, Woodrow Wilson, vetoed this legislation but Congress overrode him.

During WWI, long established empires, like the Austria-Hungary Empire and Ottoman Empire, were dismantled. Additionally, the Russian Revolution at the start of the war, along with the Armenian Genocide, added to the inescapable chaos taking over Europe at the time. Citizens of those places that had descended into “anarchy, bolshevism, and syndicalism” (in the words of Congressmen Paul B. Johnson of Mississippi) wished to immigrate to the United States. Many members of Congress, along with much of the public, worried that those systems of rule could be brought to the United States with Immigrants. Congress and the public also worried about how an influx of Immigrants would affect the workforce, the economy, and the overall culture of the United States. So in the aftermath of WWI and the start of the 1920s, Congress realized they would need stronger immigration legislation if they were to achieve their semi-isolationist goals. The Immigration Committee headed by Republican representative, Albert Johnson of Washington State, pitched a bill that would permit a number equal to 3% of the current US residents from any foreign country (recorded during a fiscal year) entrance the United States. It should be noted that this legislation did not include Asian countries listed in the Immigration Act of 1917.

Unlike those who came before him, President Warren G. Harding cooperated with Congress and hence, the Emergency Quota Act came to be. The “emergency” act was proposed by the Immigration Committee as a temporary measure that would actually limit immigration into the country. However, it’s now known that the act remained permanent as it was built upon and solidified in 1924.

Albert Johnson, Representative of Washington State

Albert Johnson was elected into the House of Representatives in 1912 for the Sixty-third Congress. Prior to his time as a state representative he worked as a journalist for many different newspapers. This line of work would have made him very familiar with public opinions of his time, making him a good candidate to represent them in Congress. According to his biography on the archival website for the House of Representatives, he served as a “captain in the Chemical Warfare Service” during WWI. Although, his most notable work was done as chairman of the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. He served in this role from the Sixty-sixth Congress to the Seventy-first. During this fever of worry and craving for isolationism that ran rampant among Congress and the public, Johnson was able to avoid the tunnel vision on the matter that afflicted his fellow congressmen.

“His tactics and comments show that he was aware of the contradictions and divisions surrounding the immigration debate. He was, unlike many restrictionists of the time, possessed of the will, vision and subtlety to attempt to marshal and sustain continued opposition to unrestricted immigration.”

Allerfeldt, Kristofer. “‘And We Got Here First’: Albert Johnson, National Origins and Self-Interest in the Immigration Debate of the 1920s.” Journal of Contemporary History 45, no. 1 (2010): 7–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40542903.

At the time, Johnson’s ability to see the whole issue and not just one side made him the ideal candidate for the attempt and achievement of a resolution to the “immigration issue”. The proposal and passing of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 was considered a step in the right direction, but the success was short lived. As someone who was aware of both sides, he knew that a complete halt to all immigration would be impossible to achieve in actuality. Which is why the Quota Act greatly reduced the number of Immigrants allowed into the United States, and did not completely halt all entry. He expressed in a press briefing that he aimed to limit immigration to “the close blood relatives of naturalized citizens.” His opponents in the Senate felt that even this exception would allow too many “undesirables” into the United States. Over the course of the next few years, Johnson would make many attempts to give each side what they wanted. It seems his efforts reached a “happy” conclusion for Congress with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924.

Bumps in the Road

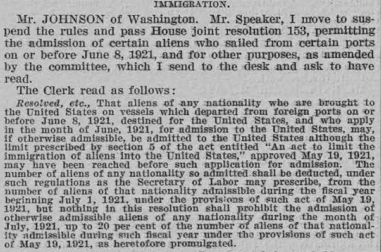

While there was discourse following the passing of the Emergency Quota Act, Congress was mostly satisfied with their bill. The trouble came after the passing of the bill, when certain aspects still needed to be worked out. One of the first issues with the terms of the legislation was the matter of the month of June, 1921. According to the Congressional Record from June 20, 1921 there was an issue with ships that departed between the passing of the bill on May 19, 1921 to June 8, 1921 that were in the the process of transporting people to the United States. The issue was whether or not to count these people toward the newly established quotas for their countries of origin, in addition to whether or not they should be allowed entry into the country.

The image above describes House joint resolution 153 of the Sixty-seventh Congress of the United States. It was proposed by none other than aforementioned Representative Albert Johnson. Johnson’s resolution was very simple, and realistic: those the ships that sailed between the passing of the act on May 19th and June 8th and the ships that were already in the process of sailing to the United States should be admitted as part of a grace period. Johnson argued that the fifteen day grace period to “clear the seas” was not enough, as ships can sail slower than expected or communications about the legislation could not have reached departing ships in time. This seems like a reasonable conclusion considering the fact that these would be the last large arrival of immigrants for the foreseeable future due to the Quota Act. However, that was not the case. Despite Albert Johnson’s reasonable argument for admittance, his opponents felt differently. Specifically, Representative Paul B. Johnson of Mississippi.

Representative Paul B. Johnson made the argument that proper communications had been made to foreign countries and ship companies following the enactment of the Emergency Quota Act on May 19, 1921. He expressed that the resolution was for the ship owners more than the people on them. In summary, if the United States was to reject the incoming Immigrants, the ship owners would be obligated to transport them all back to the port of origin free of charge. He claims that the ship owners and the governments of the original port countries were informed of the new legislature but decided to send the people anyway.

“During the hearings before the Immigration Committee it was developed that the owners of the ships carried the immigrants who now seek entrance into the United States in excess of the quota allowed under the immigration bill, and the immigrants on the said ships were informed of the passage of the law and knew of the conditions that prevailed in this country regarding immigration.”

Congress.gov. “Congressional Record.” March 1, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1921/06/20/61/house-section/article/2760-2790.

After much debate on the matter, from the ethics and morals to the legitimacy of the legislature they passed, the resolution passed with 189 “Yeas” and 71 “Nays”. Interestingly though, 169 members of the House of Representative did not vote on this resolution.

Public Perception

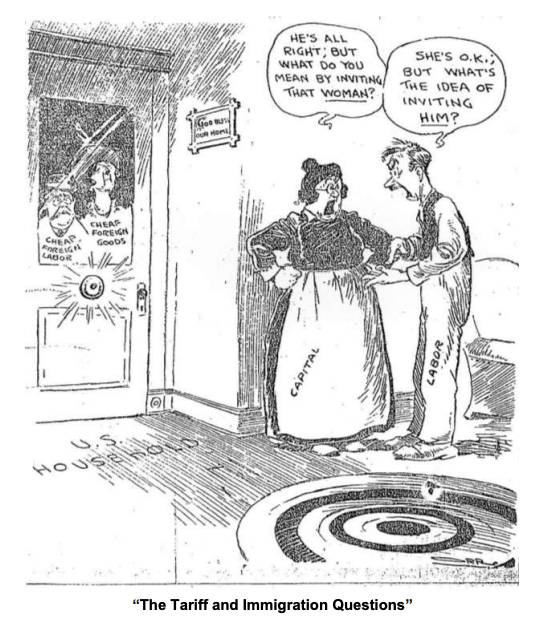

It’s easy to gather based on the remarks of the representatives in Congress that there was a decent majority of citizens who were pleased with the passing of the Emergency Quota Act. However, there were also those who harbored criticisms of the bill. These criticisms and other reactions to the bill can be seen in the following political cartoons.

This cartoon was published in the Chicago Daily Tribune on March 1, 1921, and was drawn by cartoonist Carey Orr. The couple in the cartoon, Capital and Labor, live inside the “US Household” and in this comic plays on the feeling of jealousy within a relationship. Capital feels the woman, “Cheap Foreign Goods” will replace her and Labor feels the man, “Cheap Foreign Labor” will replace him. Which in reality was one of the reasons Americans wanted stricter immigration laws, so they could remain in the jobs and roles.

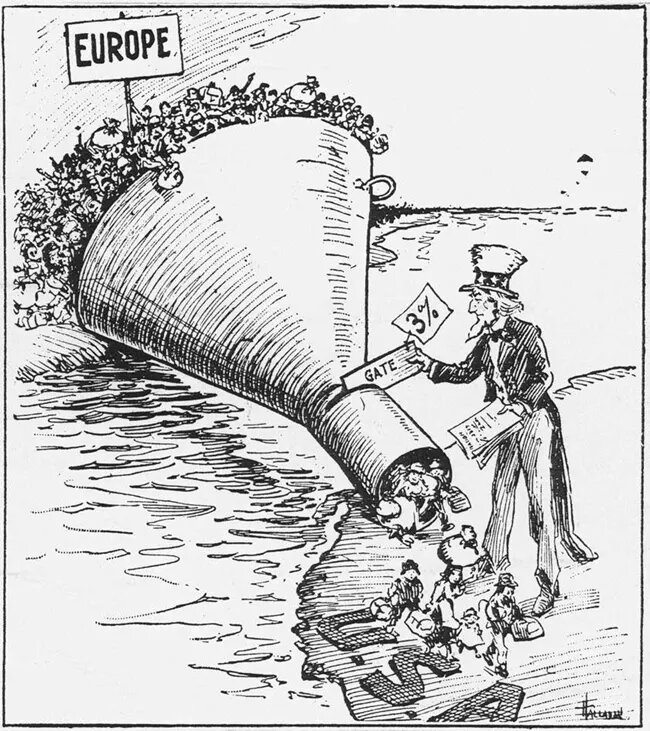

The original paper this cartoon was published in and its author are unknown, but the message is clear to see. However, whether this is a criticism or observation is unclear. Although, it feels like a criticism due to the way the bill is being depicted with Uncle Sam making all the European Immigrants go through a funnel to enter the country. All in all, the political cartoons of the time give much insight to the way the Emergency Quota Act was perceived by the public.

Significance

The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 marked the beginning of the end for major waves of Eastern and Southern European immigration to the United States. It also seems to be the origin for many of the arguments used today against South American and Mexican immigrants. The close look done at the legislation one hundred years later illuminates how the ideals and notions Americans have surrounding immigration have not changed, but shifted from group to group. However, this event is truly a reflection of its time. After WWI the world was adjusting to the many upheavals that were arising all over Europe. Since its founding the American government had always strived to achieve some form of isolationism to protect its democratic-republic system, as George Washington had recommended. So, when long standing Empires, revolutions,genocide, and World War began their reaction was to protect themselves, and America, first. Which resulted in a decade of a healthy economy and much growth throughout other areas of American living. Which is why the budding stifling of immigration in the 1920s, while unfortunate, does not complicate the way the 1920s are remembered today.

Bibliography

Allerfeldt, Kristofer. “‘And We Got Here First’: Albert Johnson, National Origins and Self-Interest in the Immigration Debate of the 1920s.” Journal of Contemporary History 45, no. 1 (2010): 7–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40542903.

Bureau, US Census. “Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1922.” Census.gov, December 16, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1923/compendia/statab/45ed.html.

“Closing the Door on Immigration (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, July 18, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/articles/closing-the-door-on-immigration.htm.

Congress.gov. “Congressional Record.” March 1, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bound-congressional-record/1921/06/20/61/house-section/article/2760-2790.

History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “JOHNSON, Albert,” https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/J/JOHNSON,-Albert-(J000114)/ (March 01, 2023)

McSeveney, Sam. “Immigrants, the Literacy Test, and Quotas: Selected American History College Textbooks’ Coverage of the Congressional Restriction of European Immigration, 1917-1929.” The History Teacher 21, no. 1 (1987): 41–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/492801.

Higham, J. Strangers in the Land. Cambridge, MASS: Athenseum Press, 1963.

Michelle Steidle is a History Major at Ramapo College, graduating with the Class of 2023. She enjoys historical research, long walks on the beach, and a good joke.