The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 was an act that on its surface gave more structure to the increasing number of plans for a highway system across the U.S. and to the federal aid allotted for highway construction. The act arose as a solution to the debate about whether the U.S. government should focus on building long-distance or farm-to-market roads. Developed by Thomas H. MacDonald, director of the Bureau of Public Roads, in tandem with the American Association of State Highway Officials, the act favored desires for more farm-to-market roads, otherwise called county roads, and rejected the idea of a national highway network. It restricted federal aid to a specific system of federal-aid highways, which were “not to exceed 7 percent of all roads in the state” and three-sevenths of which “must consist of roads that are ‘interstate in character.’”1

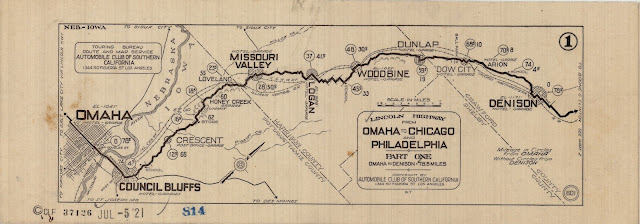

This act was only one piece of a much larger move towards an integrated highway system that began in 1916 with the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. Project decisions and implementation were handled at a state level, however, causing disjointed improvements of roads that made it difficult to oversee progress across state lines. Along with the diversion of World War I, this led to a need for change by the war’s end in the late 1910s.

The debate about long-distance roads versus farm-to-market roads reflects a larger conflict between the old and the new within society during the 1920s. The 1920s brought much change and growth, both financially (at least for some) and culturally. Many of these cultural changes brought in modern ideas that pushed back against the more conservative way of thinking that stemmed from the Victorian era. Lynn Dumenil discusses this in “The Acids of Modernity: Secular and Sacred Interpretations” chapter of The Modern Temper. She mentions that women’s emerging role in the workplace and politics, shifts in social organization because of new mass culture and technology, a rise in urban culture, and an increase in bureaucratization challenged the older worldview that allowed and encouraged order and hierarchy as well as racism, sexism, and nativism.2

It’s important to consider that as consumers bought cars, which Dumenil described as one of the “symbols of the new order,” more frequently throughout the early 1900s and into the 1920s, this impacted the need for improvement to road infrastructure.3 In addition, if more people had the means to drive farther around the country, they needed well-maintained roads to travel, many of which were not instated yet. Thus, the creep of modernity in the 1920s influenced the need for highways, federal funding for highway construction, and, therefore, the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921.

The debate about long-distance or farm-to-market roads also represented the push and pull between the old and the modern. Advocacy for a large national highway system can be viewed as in alignment with modern or progressive ideals, such as those that supported the increase of cars, more federal intervention and regulation, and so on. On the other hand, the support for maintaining and creating smaller farm-to-market roads with construction projects that would remain under state supervision leans more towards the older beliefs.

Seeing as the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 was meant to appease those who did not support long-distance roads, the act can viewed as a win for the older ideals. Set against the larger history of plans for highway systems both before and after the act, The Modern Temper helps put the act in the cultural context of the 1920s. With how the U.S. highway system is set up today, the long-distance road advocates clearly prevailed, so the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 can seem out of place. Context about how the 1920s was a generally tumultuous time, especially in terms of culture with modernity and tradition in battle, helps the act’s existence make sense.

Footnotes

- Richard F. Weingroff, “From 1916 to 1939: The Federal-State Partnership At Work,” Public Roads 60, no. 1 (1996), https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/summer-1996/1916-1939-federal-state-partnership-work. ↩︎

- Lynn Dumenil, The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 88. ↩︎

- Dumenil, 88. ↩︎

Rebecca Gathercole is a senior Communications Arts major with a minor in Creative Writing.