Overview

The National Maternity and Infancy Protection Act, more commonly known as the Sheppard-Towner Act, could be viewed, out of context, as ahead of its time. While it came on the heels of women’s suffrage and the 19th Amendment in 1919, Sheppard-Towner could seem out of place when set against the glamour, parties, and excess that is stereotypically paired with the 1920s.

What people often overlook, however, is the spirit of progressivism that pervaded the early 1900s. The Progressive Era, which lasted approximately from 1890 to 1917, was a time full of social activism and political reform. While activists worked toward a variety of causes from decreasing corruption with antitrust regulation to protecting the environment through conservation efforts to creating safer working and living conditions within cities, the collective goal during the era was “to make American society a better and safer place in which to live.”1

The women’s rights movement was one of the more powerful forces during the Progressive Era. Besides fighting for women’s right to vote, there were also women’s organizations advocating for better conditions for infants, young children, and mothers, especially in light of the continually high mortality rates. The largest of these was the U.S. Children’s Bureau, a federal agency started in 1912, which became “the first female stronghold in the federal government,” according to Robyn Muncy in Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890-1935.2

While progressivism was fading after World War I and into the 1920s, the passage of the Sheppard-Towner Act proved a major success for the Children’s Bureau. The Bureau had been researching the causes of infant and maternal mortality from its start, finding links between mortality rates and poverty. In 1917, the infant mortality rate in the United States was 93.8 per 1,000 births, which translates to slightly more than one in eleven infants dying before making it to one year old.3

Even before the official passage of the Sheppard-Towner Act, the Children’s Bureau was working hard to implement reforms in child welfare, especially during World War I. Using the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, which was a wartime organization created by the federal government, Chief of the Children’s Bureau Julia Lathrop created a campaign called “Children’s Year,” which dedicated 1919 to saving “the lives of at 100,000 children under 5 years of age and to make life safer for all children.”4 The campaign included a plethora of goals that mainly dealt with healthcare access for infants and mothers, education access for children, and access to financial assistance for all families. Muncy notes that one of the reforms encompassed within Children’s Year was the creation of state and local bureaucratic agencies that oversaw all of these new programs and initiatives, which shows how “Lathrop’s professional position allowed her to keep alive and even broaden support for the female progressives’ child welfare agenda.”5 Lathrop’s moves during this time were strategic to use the resources available to help the movement better achieve its goals and can be seen as a precursor to the Sheppard-Towner Act.

Studies from the Children’s Bureau reported that around 80% of pregnant women in the U.S. at that time received no advice or training about how to care for an infant.6 The Sheppard-Towner Act was introduced as a solution. With the purpose of establishing funds from the federal government that would allow states to create clinics, educational programs, and literature for and about prenatal and infant care, a first-of-its-kind infant and maternity healthcare bill was introduced in Congress in 1918 by Montana Republican Representative Jeanette Rankin, with support from Lathrop. When that bill failed, Texas Democratic Senator Morris Sheppard and Iowa Republican Representative Horace M. Towner later sponsored a similar bill, reintroducing it to Congress a few times between 1919 and 1921. However, it only gained traction after women earned the right to vote and eventually passed through Congress in mid-1921. The Sheppard-Towner Act was signed into law on November 23, 1921 by President Warren G. Harding.

The Women’s Joint Congressional Committee (WJCC), established in 1920, played a part in getting Sheppard-Towner passed. The WJCC was a collective of women’s organizations that came together to organize support and lobby for a variety of women’s issues, with the group representing roughly 20 million people.7 For Sheppard-Towner, the WJCC showed its support in many ways, from sending a multitude of letters and telegrams to Congress to running articles in popular women’s magazines to sending representatives to testify at hearings. “Members of Congress of years’ experience say that the lobby in favor of the Sheppard-Towner bill was the most powerful and persistent that had ever invaded Washington,” wrote the Journal of the American Medical Association about the lobby.8

The eventual success of the Sheppard-Towner Act makes sense within the larger context of the early 1920s. While the spirit of progressivism certainly lingered, there is another factor that may have impacted Sheppard-Towner’s passage that cannot be overlooked. Many thought that newly enfranchised women would majorly shift election results by comprising a unified voting bloc that political candidates would need to consider and appeal to in order to secure wins. Lynn Dumenil mentioned in The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s that male politicians often tried to appease the new group of female voters by giving in to their requests. She shared as an example, “The Democratic National Convention of 1920 incorporated twelve of twenty recommendations of the newly founded League of Women Voters; the Republican Party adopted five.”9 With the Sheppard-Towner Act passing only two years after women gained voting rights, its passage could be attributed to this same phenomenon.

Impact

The Sheppard-Towner Act was initially set to provide federal funding to states for five years from 1922 to 1927, when Congress would have to choose to renew it. Although Sheppard-Towner went through a series of negotiations to pass through Congress, especially regarding which agencies would hold power over the decisions, plans, and money within the individual states, it resulted in the establishment of the Board of Maternity and Infant Hygiene that supervised and approved how each state spent its funding.10 The funding was dispersed to states through a matching system, meaning that all states were given $5,000 from the start and then could receive up to another $5000 in dollar-for-dollar funds. They could later receive more matched funding with a cap based on the state’s population.11

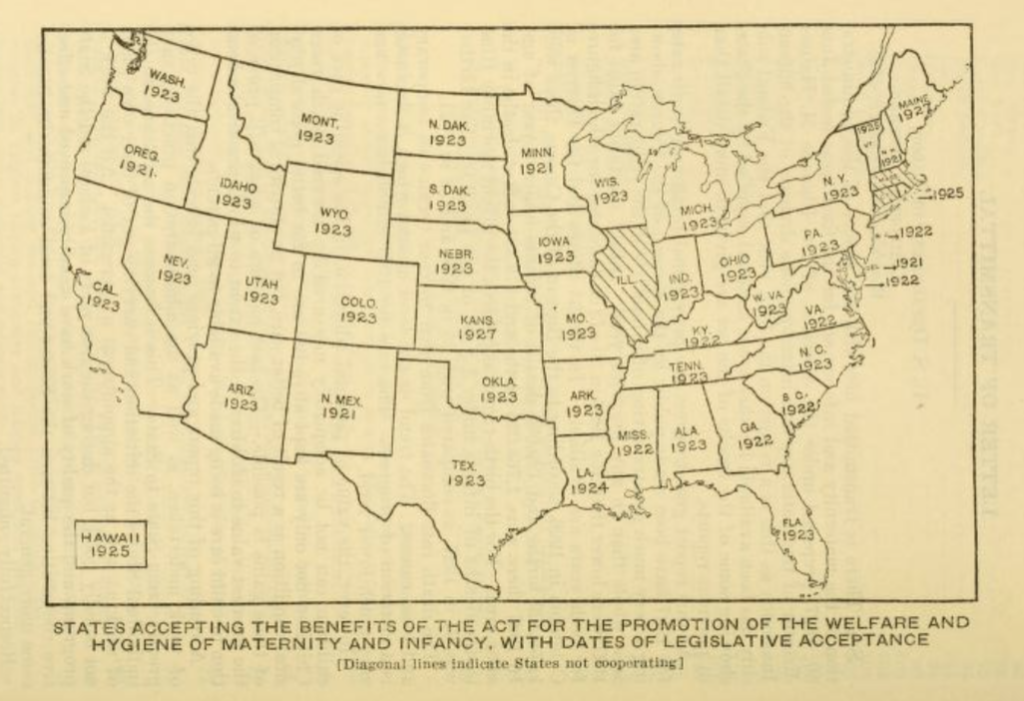

When Sheppard-Towner reached its conclusion in 1929, it had provided funding for seven years in total. The federal government appropriated nearly $10 million to fund the Sheppard-Towner Act, but with that, was able to accomplish a great deal throughout the country.12 Most states had welcomed Sheppard-Towner, and forty-five of the forty-eight states had chosen to accept the funding by 1927.13 Between 1921 and 1928, Sheppard-Towner established approximately 3,000 prenatal care clinics, 180,000 infant care seminars, more than 3 million traveling nurse home visits, and the distribution of educational literature throughout the country.14 Both the number of initiatives created and the number of people reached increased each year that the Sheppard-Towner Act funding was active.

These initiatives received much attention and praise in local newspapers throughout the 1920s. The Southern Pediatric Seminar in Saluda, North Carolina was an annual seminar started in 1921 for sharing the latest knowledge with pediatricians about children and their health. While the initial meeting had only three doctors in attendance, the 1928 seminar welcomed over 100, as reported in the Asheville Citizen-Times, and attracted knowledgeable and highly-regarded doctors to teach the courses. With the glowing headline “Saluda Seminar Is Best Yet Held,” the article sheds a positive light on the seminar, describing how those who attended in previous years gave it “the highest terms of commendation.”15

Sheppard-Towner also allowed the introduction of the “health mobile” in some states. Particularly in Ohio, the health mobile was a truck containing materials, such as electric generators, moving picture machines, films, and literature, that allowed it to quickly set up and show educational movies about health and child care wherever it went. The truck, led by Dr. H. E. Kleinschmidt toured Ohio’s counties, traveling to fairs, schoolhouses, and other public spaces, and garnering excitement within the local newspapers. The Marion Star reported in November 1925 that the health mobile found success when “appearing before record crowds at all places.”16

Not only was the Sheppard-Towner Act successful in creating accessible healthcare and educational programs, but it also led to a marked improvement in the health and survival of both infants and mothers. Sheppard-Towner saw the infant mortality rate drop from seventy-five per 1000 births in 1921 to sixty-four per 1000 by its conclusion. For mothers, the mortality rate saw a smaller decrease from 67.3 per 1000 in 1921 to 62.3 per 1000 in 1927, which is especially notable because, during the same period, the overall death rate increased slightly.17

Lathrop’s and the Children’s Bureau’s largest goal with the Sheppard-Towner Act was to reach rural communities, which remained largely untouched by previous child welfare reform efforts and adequate healthcare in general. They were successful in this goal, with journalist Frederic J. Haskin pointing out in his 1929 reflection about Sheppard-Towner that through the focus on rural areas, the mortality rates for both infants and mothers had decreased there. He wrote, “There has been much work… in the scattered regions of many states where there are whole counties without a single physician.”18 The Children’s Bureau 1927 “The Promotion Of The Welfare And Hygiene Of Maternity And Infancy” report showed that while there was great variation in how much the average infant and mortality rates decreased between 1917 and 1926, they overall trended downward in rural areas. The largest decrease in infant mortality rate was 14.1% in Pennsylvania while for maternal mortality rate, it was a 35.9% decrease in Utah.19

Despite Congress’ concern and attempt to avoid agencies like the Children’s Bureau gaining too much power over the execution of the Sheppard-Towner Act, the Bureau’s focus on rural areas provides a clear example of how they worked around Congress’ efforts. They would reject proposals that did not center rural constituents, even though Congress had denied the original wish for funding to be solely designated to those areas. They also took liberties in denying that funds be used for volunteer organizations.20 By finding these loopholes, the Children’s Bureau was able to use the Sheppard-Towner Act to garner a “monopoly over child welfare policy,” as Muncy described it.21

Opposition & Demise

For all the success that the Sheppard-Towner Act achieved, it certainly did come with flaws and faced a copious amount of opposition and criticism. There was resistance to general child welfare reforms long before the Sheppard-Towner Act existed with one New York newspaper criticizing Lathrop’s work at the Children’s Bureau by saying, “Out through the south and west, her army of trained women is moving on the households of the poor, attacking the city and village that does not insure its babies pure milk.”22 While this account certainly overdramatizes the Children’s Bureau’s work, it does reflect some of the concerns that opponents had with child welfare reform, which only continued with the introduction of Sheppard-Towner.

There were a variety of reasons that people opposed the Sheppard-Towner Act — including fears that it was tied to a communist or socialist plot, or claims that it interfered with states’ rights — but a main one that came up before its passage and then again in discussions of its renewal in 1927 and 1929 was from medical practitioners and organizations. Some viewed Sheppard-Towner as a means for “the regular medical profession to eliminate all but orthodox practices,” but the strongest opposition came from physicians in the American Medical Association, which put up a tirade against it for its entire eight-year existence.23

As the Sheppard-Towner Act was implemented, many took issue with how invasive the Children’s Bureau’s approach could be. Because many of the workers and nurses traveled from county to county to provide conferences and seminars about child care or to visit individual homes, many felt that it represented “a sort of motherhood patrol” that put pressure upon mothers to attend events or allow strangers into their homes, without much agency to dissent.24 A subsection of the critics included many women of color, foreign-born women, and older women, who, possibly because of their identities, were resistant to new practices that differed from their cultural norms or the practices they were familiar with.

Considering that the Sheppard-Towner nurses were often middle-class white women who were quite adamant about their more scientific ways, the women’s skepticism is understandable. There was a degree of racism and cultural prejudice that permeated some of the Children’s Bureau’s processes and teachings. A prominent example is the Bureau’s treatment of and attempts to control midwifery, which by the 1920s was largely rooted in immigrant and African-American communities. The Bureau targeted midwifery as one of their concerns under the Sheppard-Towner Act, even though most states regulated it by 1921, and worked to survey midwives’ practices throughout the country. Many midwives were often convinced to enroll in nurses’ courses, with nearly 25,000 attending 2,300 in 1924 alone.25 However, the Bureau’s concerns went further, to the point where it was reported that nurses were inspecting midwives’ morality and characters. Muncy states that the “supervision of midwives went so far beyond these legitimate requirements that it proved the most intrusive of Sheppard-Towner initiatives.”26

This might come as no surprise though, seeing to what great lengths the Children’s Bureau went to exert its control over the Sheppard-Towner Act initiatives overall. The largest flaw within the system perhaps was its rigidity. There was often no room for nuance or flexibility within the nurses’ teachings, insisting that their practices were the only ways to raise a healthy child. Many also believed that good motherhood consisted only of taking on domestic roles and caring for children. Muncy said it best when she wrote that “one of the cruel ironies of this history is that professional women used their hard-won positions of public authority to advocate for the limitation of opportunities for the majority of women, who were mothers.”27

However, it wasn’t women alone, but also men with governmental power, who ultimately led to the Sheppard-Towner Act’s downfall. When Sheppard-Towner was set to expire in 1927, the renewal faced opposition in the Senate from the American Medical Association, Woman Patriots, and other organizations for nearly eight months but was eventually extended for two years under the condition that it would be repealed in 1929.28 The WJCC among others made efforts in 1928 to save Sheppard-Towner, even going so far as to introduce a new, laxer child welfare bill, but nothing was able to prevent its end on June 30, 1929.

Perhaps the main reason that Sheppard-Towner was unable to regain support was that male politicians no longer feared the female voting bloc. As the years passed in the 1920s, it became clear that women did not comprise a singular voting group but rather the intersections of their identities affected how they voted. The 1920s, however, were also marked by a general fading progressive spirit and a rising distrust of federal intervention. Dumenil expressed how public opinion had changed when she wrote, “Resentment of federal power… was a widespread sentiment that politicians and business interests, eager to keep private enterprise unfettered, manipulated to oppose specific reform legislation.”29 With a weakened women’s rights movement and far removed from the strong desires for reform of the 1910s and early ‘20s, it made it much easier for politicians to passively allow or even root for Sheppard-Towner’s expiration without fear of much backlash.

Significance

While the Sheppard-Towner Act was a short-lived but powerful piece of legislation that managed to pass as a remnant of the Progressive Era, its significance in both the short- and long-term cannot be overstated. It is often overlooked as a piece of 1920s history, especially amongst all the bigger and brighter events and cultural moments that have become stereotypically associated with the period, but it radically reshaped how the U.S. approached healthcare and education, especially for women and children, while saving thousands of lives. Regardless of any of the flaws or the debate that surrounded it, that fact in itself makes the Sheppard-Towner Act worthwhile.

Beyond that, it also was one of the earliest and most comprehensive pieces of social security legislation in U.S. history. The Sheppard-Towner Act served as a precursor to many of the New Deal welfare programs that President Franklin D. Roosevelt instated in the 1930s and ‘40s, most notably the maternal and child welfare protections in the Social Security Act of 1935. Thus, perhaps unknowingly, remnants of the Sheppard-Towner Act still reverberate within the processes of today’s U.S. healthcare and welfare systems.

Citations

Footnotes

- “Overview,” Library of Congress, accessed March 19, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/progressive-era-to-new-era-1900-1929/overview/. ↩︎

- Robyn Muncy, Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890-1935, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 38. ↩︎

- “Birth Statistics and Infant Mortality: Preliminary Report of the Bureau of the Census for 1917,” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 34, no. 26 (1919): 1426, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4575212. ↩︎

- Julia Lathrop, Speech Before Alabama Educational Union, March 28, 1918, folder 9, box 60, Abbott Papers, quoted in Muncy, 98. ↩︎

- Muncy, 98. ↩︎

- J. Stanley Lemons, “The Sheppard-Towner Act: Progressivism in the 1920s,” The Journal of American History 55, no. 4 (1969): 777, https://doi.org/10.2307/1900152. ↩︎

- Lemons, 778. ↩︎

- Journal of the American Medical Association, 77 (Dec. 10, 1921), 1913-14, as quoted in Lemons, 779. ↩︎

- Lynn Dumenil, The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 61. ↩︎

- Muncy, 106. ↩︎

- Carolyn M. Moehling and Melissa A. Thomasson, “Saving Babies: The Contribution Of Sheppard-Towner To The Decline In Infant Mortality In The 1920,” NBER Working Paper Series (2012): 3. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor and Children’s Bureau, “The Promotion of the Welfare and Hygiene of Maternity and Infancy: The Administration of the Act of Congress of November 23, 1921, Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1927,” (Book, Washington, DC, 1928), 2-3. ↩︎

- Muncy, 107. ↩︎

- Katherine Madgett, “Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act (1921),” May 18, 2017, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/sheppard-towner-maternity-and-infancy-protection-act-1921. ↩︎

- “Saluda Seminar Is Best Yet Held,” Asheville Citizen-Times (Asheville, NC), July 26, 1928. ↩︎

- “‘Healthmobile’ Completes Tour of Union County Towns,” Marion Star (Marion, OH), Nov. 10, 1925. ↩︎

- Lemons, 785. ↩︎

- Frederic J. Haskin, “Has Federal Aid Saved Baby Lives?,” Asbury Park Press (Asbury Park, NJ), May 24, 1929. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor and Children’s Bureau, 37-39. ↩︎

- Muncy, 108. ↩︎

- Muncy, 109. ↩︎

- “War Will Kill Our Men; Don’t Let Sun Kill Our Babies!,” Gazette (Niagara Falls, N.Y.), Aug. 2, 1917, bound volume, box 43, Grace and Edith Abbott Papers, Special Collections, Univ. of Chicago Library, as quoted in Muncy, 93. ↩︎

- Lemons, 780. ↩︎

- Muncy, 111-12. ↩︎

- Muncy, 116. ↩︎

- Muncy, 116. ↩︎

- Muncy, 122. ↩︎

- Lemons, 784-85. ↩︎

- Dumenil, 66. ↩︎

Bibliography

- “Birth Statistics and Infant Mortality: Preliminary Report of the Bureau of the Census for 1917.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 34, no. 26 (1919): 1426–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4575212.

- Dumenil, Lynn. The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

- Lemons, J. Stanley, “The Sheppard-Towner Act: Progressivism in the 1920s.” The Journal of American History 55, no. 4 (1969): 776–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/1900152.

- Madgett, Katherine. “Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act (1921).” May 18, 2017. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/sheppard-towner-maternity-and-infancy-protection-act-1921.

- Moehling, Carolyn M. and Melissa A. Thomasson, “Saving Babies: The Contribution Of Sheppard-Towner To The Decline In Infant Mortality In The 1920.” NBER Working Paper Series (2012).

- Mozer, Deborah. “For Mothers and Children: The Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921.” 1998. http://hdl.handle.net/10822/1051380.

- Muncy, Robyn. Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890-1935. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- “Overview.” Library of Congress. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/progressive-era-to-new-era-1900-1929/overview/.

- U.S. Department of Labor and Children’s Bureau. “The Promotion of the Welfare and Hygiene of Maternity and Infancy: The Administration of the Act of Congress of November 23, 1921, Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1927.” Book, Washington, DC, 1928.

More Resources

- Baker, Jeffrey P. “When Women and Children Made the Policy Agenda — The Sheppard–Towner Act, 100 Years Later.” The New England Journal of Medicine 385, no. 20 (2021): 1827–1829. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMp2031669.

- Brown, Dorothy Kirchwey. The Case for Acceptance of the Sheppard-Towner Act. Washington, D.C.: National League of Women Voters, 1923.

- Brown, Dorothy M. Setting a Course: American Women in the 1920s. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1987.

- Karsh, Andrew and Shanna Rose. “3 – The Brief Life of the Sheppard–Towner Act.” In Responsive States: Federalism and American Public Policy, 58 – 83. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Rebecca Gathercole is a senior Communications Arts major with a minor in Creative Writing.