In the entire record of aviation history, few feats capture the imagination quite like Charles Lindbergh’s solo transatlantic flight. On May 20th, 1927, a young airmail pilot who had dropped out of college to be a stunt pilot, defied the odds and flew over the deep blue expanse of the Atlantic Ocean, piloting the Spirit of St. Louis from New York to Paris in a whopping 33.5 hours. This wasn’t just a record-breaking flight; it was a cultural phenomenon that ignited a global obsession with aviation and forever changed the way people perceived the possibilities of flight to this day.

Before the flight

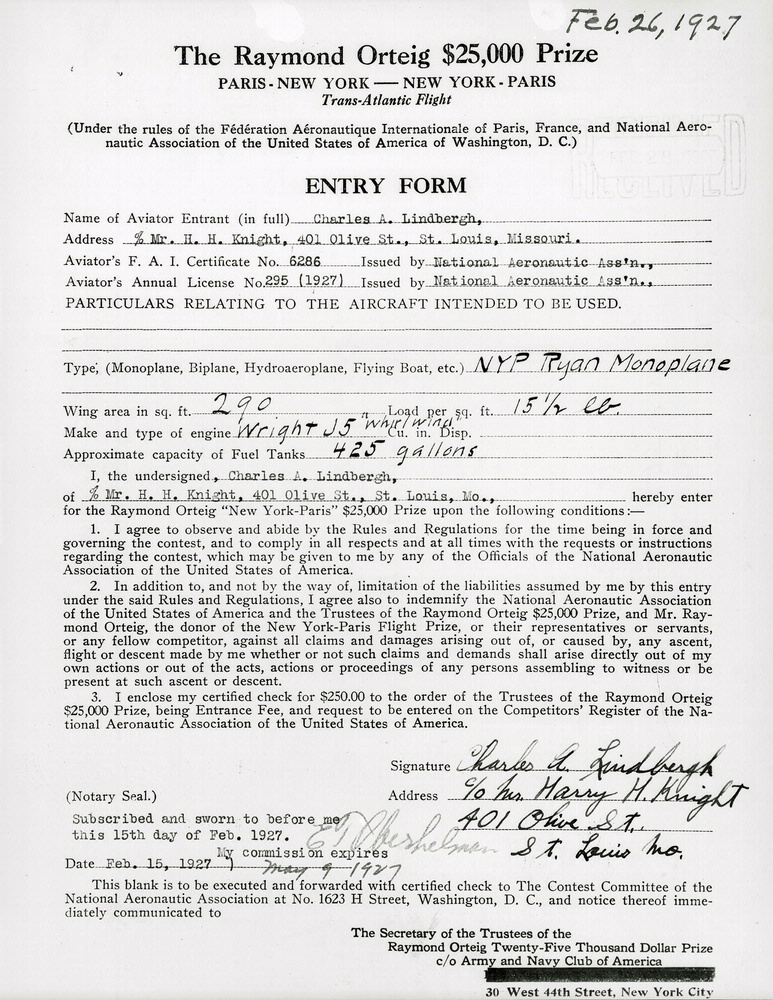

The foundation of Lindbergh’s transatlantic adventure was built several years prior. In 1919, Raymond Orteig, a New York hotelier of French descent, offered a huge $25,000 prize to the first person who could complete a nonstop flight from New York City to Paris. This courageous challenge, fueled by the swelling spirit of competition in the early days of aviation, attracted a host of daring aviators. Several attempts were made in the years leading up to 1927, each ending in disappointment. Some aircraft were ill-equipped for the long journey, succumbing to mechanical failure or the unforgiving elements. Others, crewed by multiple pilots, simply didn’t have the stamina or navigational expertise to conquer the vast emptiness of the Atlantic. A few pilots died or were severely injured in their quest.

While others were making attempts to overcome this record and win the prize, Lindbergh was busy with his own life. Quitting the University of Wisconsin in 1922 to fly planes because of his interest in flight after World War I, Lindbergh took flying lessons at Nebraska Aircraft Corporation, where he gained experience in mechanics and parachute jumping. He started his aviation career as a barnstormer, a person who travels the country selling plane tickets and performing aerobatic stunts for entertainment. In 1924, he joined the United States Army Air Service, and earned the rank of second lieutenant, but there was no need for active duty pilots, so he quickly returned home, and in 1925, was hired as a chief pilot for Robertson Aircraft Corporation, flying airmail between Chicago, and his home in St. Louis.

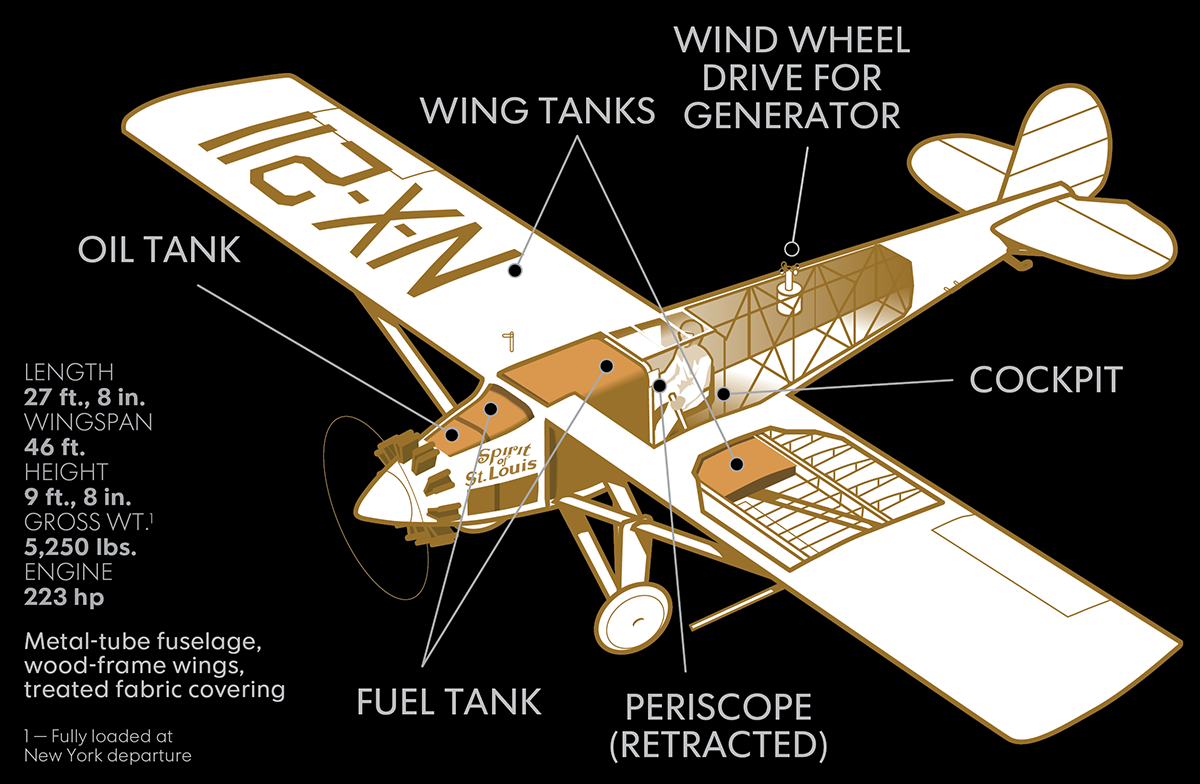

After these career changes, Lindbergh emerged as a serious contender for the $25,000 prize in early 1927. He possessed an unwavering confidence in his abilities and a meticulous approach to planning. Unlike other competitors relying on heavily modified bombers, Lindbergh had a lighter, single-engine design in mind. He convinced a group of St. Louis businessmen to back his vision, and Ryan Airlines in San Diego, California constructed the now-iconic Spirit of St. Louis. The Spirit of St. Louis was a feat of aeronautical engineering for its time. It was a lean, purpose-built monoplane, prioritizing fuel efficiency and range over passenger comfort. The airline company changed one of their Ryan M-2 aircraft to have a longer wingspan and fuselage and additional struts to hold up the weight of the extra fuel. Lindbergh participated heavily in the design process, ensuring the cockpit met his specific needs for navigation and instrument control. He tailored it to fit him “like a suit of clothes” .He cut every bit of weight he could from the plane so it could hold as much fuel and gas tanks as possible. One gas tank was mounted between the engine and the cockpit, blocking his view through the windshield, so he only had his instruments to guide him, one being a retractable periscope, an outer case with mirrors at each end set parallel to each other at a 45° angle that he could slide out the left side window for limited view. This was actually the first use of an instrument like this on a plane. The engine was built by Wright Aeronautical, the aircraft manufacturer founded by the Wright brothers. Now, Lindbergh had a one-of-a-kind aircraft to achieve his aviation goals.

Taking off from New York and landing in Paris

On May 19th, Lindbergh and mechanics checked over the plane’s engine and navigational instruments and flew the plane a few times over Roosevelt Field on Long Island, the place that he would be taking off from early the next morning. The single engine sputtered and coughed on several occasions, forcing Lindbergh to troubleshoot and make some repairs, his mechanical knowledge coming into play.

On the dreary morning of May 20th, a crowd gathered at the field to witness the start of Lindbergh’s huge undertaking. The weather was less than ideal, with rain and low visibility affecting the takeoff. Despite some concerns, Lindbergh felt undeterred. The weather forecasts for his route looked good enough for him. At 7:40 am, the engine of the plane was started, and at 7:52, Lindbergh headed the Spirit of St. Louis into the sky, embarking on a journey fraught with danger and uncertainty.

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean was not an easy task. Lindbergh battled fatigue, after barely sleeping the night before due to nerves. He zipped his flight jacket and put on his mittens, but not his boots, for the fear that he would be too warm and become sleepy. Throughout the flight, he relied on sandwiches and water to sustain himself. He experienced good weather in the beginning of his trip, but then ran into icy conditions that made him consider turning around. There were news reporters following him to document the story, but they turned around about half way into the flight because of the tumultuous weather. He flew through storm areas and cloudbursts, as well as coastlines covered with fog. He also left the plane’s side windows open, hoping that the rain and cold air would keep him awake. Lindbergh navigated by the stars and rudimentary techniques, showing his exceptional piloting skills. There was a thick haze covering most of the sky, only stars directly overhead could be seen; there was no moon in the sky that night. As he attempted to fly through some of the larger clouds, sleet collected on the plane and forced him to turn around and get back into clear air. He averaged around 100 miles per hour and the altitude varied from just above the waves to about 10,000 feet during the night. The vast expanse of the ocean offered no solace, its relentless waves a constant reminder of the dangerous nature of his mission. In the morning, the sun came up, but he was still forced to navigate by instruments only, since he still had to fly through the clouds. The sun made the cockpit hot and his legs were cramping. The fog was sporadic, covering some portions of the flight completely, and other times disappearing, making navigation a lot easier. At times, he flew so low to the ocean and shorelines, that he could see fishing boats and talk with fishermen along the beach.

Later on, about 20 years later in his writings, he reported that he had hallucinations about ghosts while in the air. Little friendly apparitions would come to visit him and give him tips on flying, and navigation as well as encouragement. Sometimes there were just one or two, other times there were a group of them. He wasn’t scared of them, he felt like they were his buddies helping him along in his journey.

The flight path Lindbergh embarked on is known as a “great circle” route from New York to Paris. He flew from New York, along the coast of Newfoundland and over Ireland to reach his final destination. This was the shortest route for him to take.

After what seemed like an eternity, a glimmer of hope emerged on the horizon. On May 21st, Lindbergh spotted the faint outline of a coast and changed his course to the nearest point of land to be sure it was the coast of Ireland. He located Cape Valentia and Dingle Bay, and then changed his compass back to Paris.

News of Lindbergh’s impending arrival had spread like wildfire across Europe. By the time the Spirit of St. Louis touched down at Le Bourget Field in Paris at 10:24 pm, or 5:00 pm New York time, an excited crowd of over 150,000 people gathered at the French airfield to witness the historic moment. Lindbergh emerged from the cockpit, a tired but triumphant figure, instantly thrust into the international spotlight. He took one step from the plane but then was dragged the rest of the way. For over thirty minutes, he was hoisted around the crowd before the French military stepped in and was able to get him out of the situation. He was planning on staying and visiting some of the European countries, but returned to the United States shortly after. He realized that people were waiting for him, and President Coolidge sent a ship for him to come back to America.

Overnight, Lindbergh became a global celebrity. He was showered with accolades, including the Distinguished Flying Cross medal from President Calvin Coolidge and later on a Medal of Honor, the highest military award. There were also ticker-tape parades thrown when he would come to different cities, usually attended by three to four million people, and an overall hero’s welcome wherever he went. He also became a colonel in the Air Corps Reserve. Time magazine honored him as the first Man of the Year in 1928. Herbert Hoover appointed him to the National Advisory committee for Aeronautics and gave him a congressional Gold Medal in 1930.

The “Lindbergh Boom” and the 1920s: A Symbol of Hope for a Changing World

The transatlantic flight significantly impacted the 1920s in several ways. It ushered in the “Lindbergh Boom,” a surge in public interest in aviation. Lindbergh flew a tour of the 48 states as well as Mexico, sponsored by Harry Guggenheim from Long Island, New York. Investment in aerospace research and development increased dramatically. In 1927 alone, there was a 300% increase in the number of pilot licenses and an increase of over 400% of the number of licensed aircraft. Public fascination with flying fueled the growth of commercial aviation, with airlines seeing a rise in bookings and a growing market for passenger travel. The number of landing fields and airports in America doubled over the next few years. This, in turn, facilitated international trade and cultural exchange.

Today, his plane is on permanent display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C, after he donated it in 1928 to the Smithsonian Institution. Lindbergh’s accomplishment resonated beyond its technological significance. He also wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning book about his experience. After his experience, he tried to stay out of the public eye and married Anne Morrow in 1929. They had thirteen children, two who passed away. Lindbergh passed away on August 26, 1974 at the age of 72.

In terms of the book, Modern Temper by Lynn Dumenil and how Lindbergh’s solo transatlantic flight fits into the 1920’s, his flight was a symbol of the machine age and the advancements that technology had taken up to that point. It also highlighted the idea of leisure activities and the ideas of celebrities and how he was an “instant celebrity of extraordinary proportions” as shown by his treatment everywhere he went, and how he is still treated as a hero today.

His feat symbolized the dawn of a new era, where the once-unimaginable transatlantic journey was now a reality. This accomplishment spurred a surge in commercial aviation, paving the way for a more interconnected world. It showcased the incredible advancements in aviation technology and the indomitable spirit of human exploration. More importantly, it captured the public imagination, fostering a sense of wonder and possibility at a time when the world was still recovering from the devastation of World War I.

The 1920s were a decade marked by anxieties surrounding WWI and the rise of totalitarian regimes but also with excitement for new accomplishments. Lindbergh’s lone flight across the vast ocean symbolized a spirit of optimism and human achievement. It provided a much-needed sense of wonder and possibility in a world facing uncertainties.

If you are interested in this topic and want to read more about it, here are some supplementary sources!

- Kessner, Thomas. The flight of the century: Charles Lindbergh & the rise of american aviation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Lindbergh, Charles A. Autobiography of values. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992.

- Lindbergh, Charles Augustus. The spirit of St Louis. Charles A. Lindbergh. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1954.

- PBS’s American Experience documentary: Lindbergh’s Transatlantic Flight: New York to Paris

- Smithsonian Institution’s Pioneers of Flight exhibit: The First Solo, Nonstop Transatlantic Flight

Citations for text:

Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998.

By, HORACE GREEN. 1927. “” we” Reveals Lindbergh as More Careful than Lucky: His Own Narrative, as Well as His Biography, Demonstrates His Practical Genius “, New York Times 1923 http://library.ramapo.edu:2048/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/we-reveals-lindbergh-as-more-careful-than-lucky/docview/104099455/se-2.

Charles Lindbergh: Biography, Trailblazing pilot, baby kidnapping. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.biography.com/history-culture/charles-lindbergh.

Groom, Winston. The aviators: Eddie Rickenbacker, Jimmy Doolittle, Charles Lindbergh, and the epic age of Flight. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2013.

Lindbergh, Charles A., and Fitzhugh Green. We, by Charles A. Lindbergh; the famous Flier’s own story of his life and his transatlantic flight, together with his views on the flight, together with his views on the future of aviation. with a foreword by Myron Herrick. New York, Grosset & Dunlap, 1928.

“Charles Lindbergh and Flight.” Bill of Rights Institute. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/charles-lindbergh-and-flight.

“Charles Lindbergh at the Cradle of Aviation Museum.” Cradle of Aviation Museum. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.cradleofaviation.org/history/history/people/charles_lindbergh.html.

“Charles Lindbergh.” Charles Lindbergh | Pioneers of Flight. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://pioneersofflight.si.edu/content/charles-lindbergh.

“Charles Lindbergh.” Encyclopædia Britannica, March 22, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Lindbergh.

“Charles Lindbergh.” History.com. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/charles-a-lindbergh#spirit-of-st-louis.

“Charles Lindbergh.” SHSMO Historic Missourians, December 15, 2022. https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/charles-lindbergh/“Periscope.” Wikipedia, March 11, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Periscope

Footnotes for images:

- Bettmann. Charles Lindbergh Posing with Historic Plane. n.d. Getty Images. https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/charles-lindbergh-american-aviator-he-is-seen-here-posing-news-photo/514896882?phrase=+Charles+Lindbergh&adppopup=true.

↩︎ - “Official Entry Form from Charles Lindbergh.” Pioneers of Flight. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://pioneersofflight.si.edu/content/official-entry-form-charles-lindbergh.

↩︎ - “Charles Lindbergh and the Flight of the Spirit of St. Louis.” USA Today. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.usatoday.com/pages/interactives/spirit-of-st-louis-anniversary/.

↩︎ - “The First Solo, Nonstop Transatlantic Flight.” Pioneers of Flight. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://pioneersofflight.si.edu/content/first-solo-nonstop-transatlantic-flight.

↩︎ - “Charles Lindbergh.” SHSMO Historic Missourians, December 15, 2022. https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/charles-lindbergh/.

↩︎ - Charles Lindbergh Biography. Accessed March 27, 2024. http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/.

↩︎ - Charles Lindbergh Biography. Accessed March 27, 2024. http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/.

↩︎ - San Diego Air & Space Museum. “San Diego Air & Space Museum – Balboa Park, San Diego.” San Diego Air & Space Museum – Historical Balboa Park, San Diego. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://sandiegoairandspace.org/newsletters/article/charles-lindbergh-animatronic-debuts.

↩︎