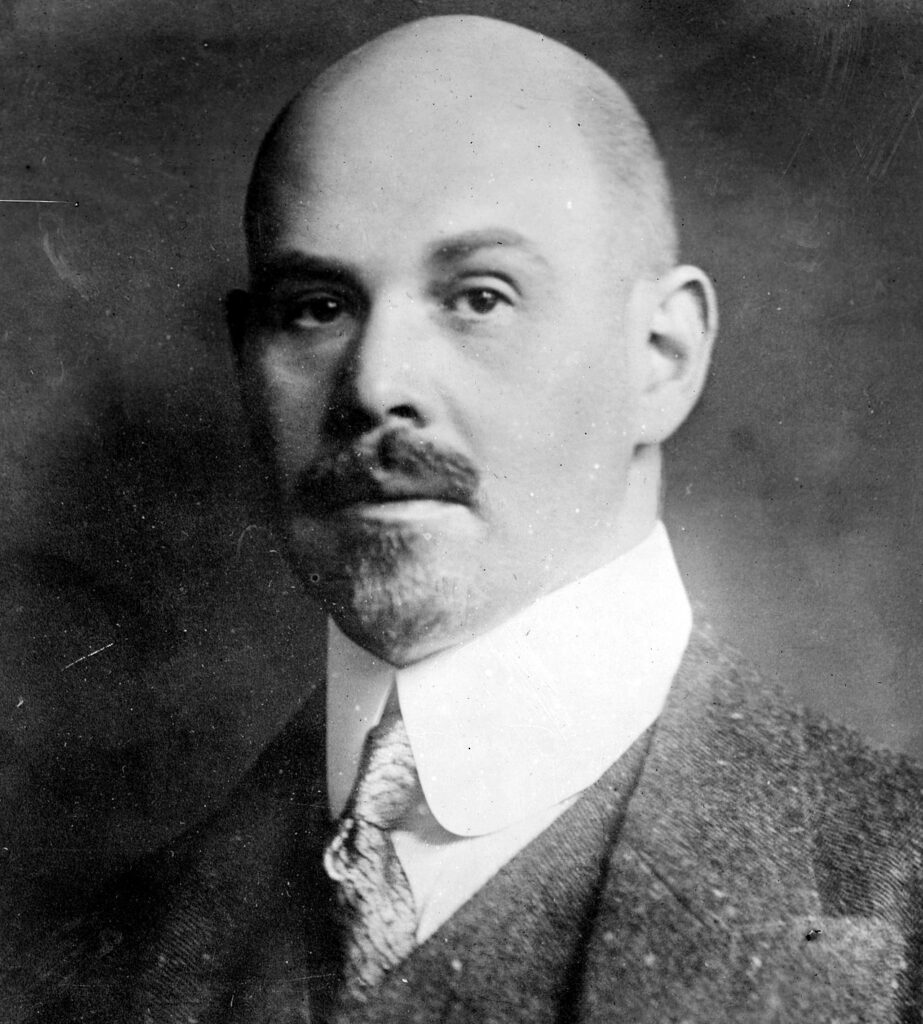

Walther Rathenau was a German statesman, industrialist, and writer who lived from 1867 to 1922. He played a pivotal role in shaping Germany’s post-World War I politics and economy, and his assassination in 1922 by right-wing extremists marked a major turning point in German politics. Rathenau was born on September 29, 1867, in Berlin, Germany. Son of Emil Rathenau, a Jewish industrialist who founded the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG), one of the largest electrical companies in Germany. Walther attended a number of prestigious schools throughout Europe, such as the University of Strasbourg and the University of Berlin, where he earned a doctorate in physics. In 1900, he was appointed to the board of directors of AEG, and he quickly climbed the company’s ladder and became CEO in 1915. During his tenure at AEG, Rathenau was responsible for a number of innovations, including the development of new electrical products and the expansion of AEG’s international operations. Rathenau was also a prolific writer and thinker, and he wrote extensively on economic, political, and social issues.

During World War I, Rathenau served as an advisor to the German government on economic matters rather than militaristic ones. He was a strong advocate for the war effort, and he believed that Germany could win the war through economic and technological superiority. However, he also recognized that the war was taking a heavy toll on German society and economy, and he called for a negotiated peace settlement. After the war, Rathenau emerged as a leading figure in the Weimar Republic, the democratic government that was established in Germany in the aftermath of the war. He served as the minister of reconstruction from 1921 to 1922, and he played a key role in rebuilding Germany’s economy and infrastructure. He also worked to improve Germany’s relations with other countries, including the Soviet Union and the United States. In 1922, Rathenau played a key role in negotiating the Treaty of Rapallo between Germany and the Soviet Union. The treaty established diplomatic relations between the two countries and provided for economic cooperation and military collaboration. This was a significant achievement as Germany had been isolated from the international community after World War I and the treaty helped to improve its standing in the world.

Rathenau’s tenure as Minister of Reconstruction was marked by controversy and conflict. He faced opposition from both sides of the political spectrum, as he tried to implement reforms aimed at modernizing Germany’s economy. Some on the left accused him of being too conservative and beholden to the interests of big business, while some on the right accused him of being too liberal and sympathetic to socialist and communist ideas. Rathenau’s most controversial initiative was his plan to reorganize the German economy through the creation of a system of corporate boards. He believed that the boards would help to streamline the economy and promote cooperation between businesses, but his critics argued that the cartels would lead to the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few large corporations. Despite the hardships faced, Rathenau oversaw the development of Germany’s infrastructure, including the construction of roads, bridges, and public buildings. He also helped to expand Germany’s telecommunications network and oversaw the development of new industries, such as aviation and electronics.

Unfortunately, Rathenau’s life was cut short by an act of political violence. On June 24, 1922, he was assassinated by members of a right-wing extremist group called the Organisation Consul. The group was composed of former soldiers, aristocrats, and nationalists who were opposed to the Weimar Republic and the perceived influence of Jewish and socialist elements in German society. The assassination was carried out by two members of the Organisation Consul, Erwin Kern and Hermann Fischer, who shot Rathenau while he was traveling in an open car in Berlin.

Work Cited

Himmer, R. (1976). Rathenau, Russia, and Rapallo. Central European History, 9(2), 146–183. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4545767

Brecht, A. (1948). Walther Rathenau and the German People. The Journal of Politics, 10(1), 20–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/2125816

Kollman, E. C. (1952). Walther Rathenau and German Foreign Policy: Thoughts and Actions. The Journal of Modern History, 24(2), 127–142. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1872561

Joe is a Sophomore at Ramapo and a Global Communications major enrolled in Discovering Digital History.