Overview

World War I began in 1914 shortly after Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. The war was fought between the Allied Powers and the Central Powers. Belgium, England, France, Greece, Italy, Japan, Montenegro, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, and the United States of America made up the Allied Powers. The Central Powers were Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany, and Turkey. The Great War ended with an armistice on November 11, 1918. At the war’s end, approximately 8.5 million soldiers were killed. Of those 8.5 million, America lost around 116,000 soldiers. Many bodies of soldiers were rendered unidentifiable from artillery blasts and other bodies had no identifiable information.

Beginnings of the Unknown Soldiers

On November 11, 1920, England buried an unknown soldier in London and France buried their unknown in Paris. Hamilton Fish Jr., also known as Fish III, was a former Army major. As a Representative (R-NY), he created and introduced House Joint Resolution 426. This resolution suggested returning an unidentified American soldier and burying him in the United States. The resolution was brought before the 66th Congress’s Committee on Military Affairs on February 1, 1921. The resolution received endorsements from war veterans Major General John Lejeune (United States Marine Corps), General John Pershing (United States Army), and from organizations such as the American Auxiliary. On March 4, the resolution was signed by President Woodrow Wilson.

American Unknown Is Chosen

On October 22, 1921, four bodies were chosen to represent the four major battles that America fought in: the Battle of Belleau Wood, the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, and the Battle of Argonne. On October 24, American World War I veteran Sergeant Edward F. Younger placed a bouquet of roses on the chosen casket. The remaining coffins were reburied and the chosen casket was transported to the awaiting USS Olympia (C-6) on the French coast. Before the Olympia left France, American Major General Henry Allen proclaimed to the Unknown, “Whoever you be, your gallant deeds are indelibly inscribed in the pages of history to the glory of your nation, and as long as free States endure will your exploits be sung.”1 “Body of America’s Unknown Soldier on Its Way Home Aboard the Olympia,” New York Times, October 26, 1921.

The USS Olympia (C-6) arrived at the Washington Navy Yard on November 9, 1921. The Unknown was carried via horse drawn carriage to the U.S. Capitol Building. The body lay in state for mourners to visit. An estimated ninety thousand mourners from the general public visited the body.

The Unknown is Buried

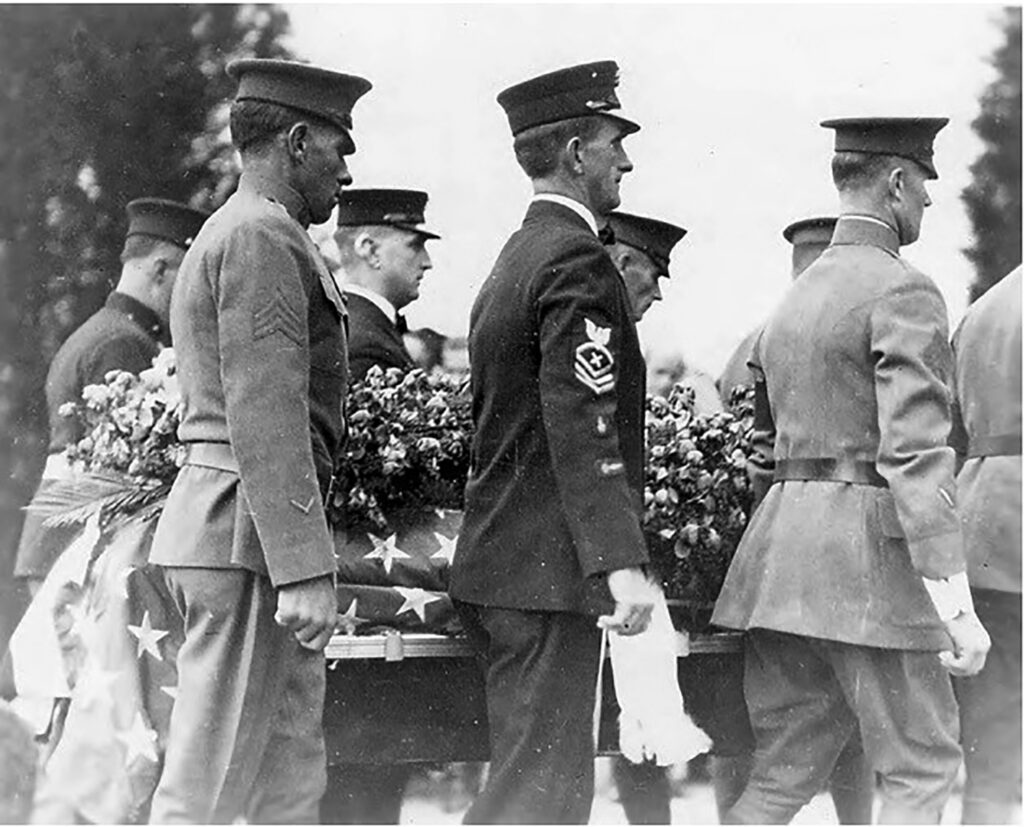

On November 11, 1921, the Unknown was carried in a five mile funeral procession from the Capitol Building to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, VA. He had eight body bearers that represented different military branches. The pallbearers included five Army soldiers, two Navy sailors , and one Marine Corps soldier. For these men, this procession allowed them to carry and bury a comrade. On battlefields, if buried, a soldier would be buried where he was killed. In the procession, there were mourners that included veterans, Red Cross nurses, and Gold Star Mothers (mothers whose sons were killed in action).

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was to be in the newly constructed Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. As part of the funeral service Bishop Charles Brent, who had served as a chaplain during the war, spoke, “Help us fittingly to honor our unknown soldiers who gave their all in laying sure the foundations of international commonwealth. Help us to keep clear the obligation we have toward all worthy soldiers, living and dead, that their sacrifices and their valor fade not from our memory.”2 Kirke Larue Simpson, “The Unknown Soldier” (Associated Press, 1921), 17. Following Brent’s speech and prayer there was a two minute nationwide silence which was issued by a presidential proclamation. These two minutes of silence are indicative of the nationwide mourning of American soldiers lost during the war.

President Harding spoke after the minutes of silence. His speech was electrically transmitted for the first time over wires that connected to amplifiers in New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco. The urge to allow as many Americans access to the funeral service as possible created the need for new technology. When President Harding concluded his speech, the Unknown was awarded with medals. The Unknown was the recipient of: the Distinguished Service Cross (America), the Medal of Honor (America), the Belgian Croix de Guerre (Belgium), the Czechoslovak War Cross (Czechoslovakia), the Victoria Cross (England), the French Croix de Guerre (France), the Medaglia d’oro al valor militare (Italy), the War Order of Virtuti Militari (Poland), and the Virtutea Militară (Romania). Chief Plenty Coups gifted the Unknown his feathered war bonnet and coup stick, which was representative of the Native Americans who served. It was also an attempt to foster good relations between Native Americans and Americans. The giving of these awards to the Unknown makes him a hero, which mirrors the way dead soldiers are seen by society. After the Unknown received his awards, he was placed in the crypt on top of French soil. The conducting of an elaborate funeral/memorial service to the Unknown shows the nation’s gratitude for those who were killed and the high regard for dead soldiers.

Although the public reaction to burying the Unknown was overwhelmingly positive and supportive, there were many who disagreed with the idea. Among those who disagreed were pacifists, socialists, and dissenters of the war. They had two main arguments: veterans were pushed aside for a meaningless effort and patriotic ideals were being pushed on the dead.

Significance

The funeral and visitation while the soldier lay in state at the Capitol building served as a surrogate funeral service for families who never received a body to bury. Mothers could mourn the Unknown as if he was their son, children could mourn him as if it were their father, and siblings could mourn him as if he were their brother. It was representative of funerals for American soldiers who lost friends or men in their charge. During the funeral ceremony Lieutenant Colonel Charles Whittlesey, an officer whose unit suffered great casualties, was quoted as saying, “I keep wondering if the Unknown Soldier is one of my men.”3 Richard Slotkin, Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality (Henry Holt and Company, 2013), 475–80. The burying of the Unknown allowed America to mourn, honor, and remember the soldiers killed in action. A quote pasted across page 2 of The Baltimore Sun, published on November 12, 1921, reads, “We Highly Resolve That These Dead Shall Not Have Died In Vain.”4 “Unknown Soldier Sleeps At Arlington,” The Baltimore Sun, November 12, 1921, p. 2.

When the Unknown was buried in 1921, the grave had a plain marker. It was thought by many Americans that this was too little of a memorial since this tomb was America’s way of honoring those killed in action, but especially those who died unidentified. Thus, in 1926, Congress allocated funds to create a more elaborate monument. A watch guard was added in 1925 to prevent the general public from disrespecting the grave site.

America was one of four total countries to bury an unknown soldier in 1921. The following Allied nations buried their unknowns: Portugal (April 6), Belgium (September 8), and Italy (November 4). Although Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were created after the war ended, they buried their own unknown soldiers in 1922. Romania buried their unknown May 17, 1923. The duty to honor war dead throughout multiple countries demonstrates the moral and emotional toll that World War I took on the countries involved.

Bibliography

“Body of America’s Unknown Soldier on Its Way Home Aboard the Olympia,” New York Times, October 26, 1921.

History.com Editors. “World War I.” History.com, January 12, 2023. https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/world-war-i-history.

House Committee on Military Affairs. Return of Body of Unknown American Who Lost His Life in the World War. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1921.

Inglis, K. S. “Entombing Unknown Soldiers: From London and Paris to Baghdad.” History and Memory 5, no. 2 (1993): 7–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25618650.

Library of Congress. “Crowd at Burial of Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery.” www.loc.gov, 1921. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c00143/.

O’Donnell, Patrick K. The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2018.

Reuters Archive. “Burial of America’s Unknown Soldier (1921).” www.youtube.com, November 24, 1921. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-yxRkk30Ck.

Royde-Smith, John Graham, and Dennis E Showalter. “World War I.” In Encyclopedia Britannica, November 23, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-I.

Simpson, Kirke Larue. “The Unknown Soldier.” Associated Press, 1921.

Slotkin, Richard. Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality. Henry Holt and Company, 2013.

Society of the Honor Guard. “Centennial of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (1921-2021),” 2021. https://tombguard.org/assets/images/news/TUS100-Advocacy-Packet_v7_122320.pdf.

———. “Timeline (1914 – 1921).” The Library of Congress, 2015. https://www.loc.gov/collections/stars-and-stripes/articles-and-essays/a-world-at-war/timeline-1914-1921/.

“Unknown Soldier Sleeps At Arlington,” The Baltimore Sun, November 12, 1921, p. 1-2.

Vleck, Jenifer van, and Timothy Frank. “From Manila Bay to Philadelphia: The Life and Service of USS Olympia.” Arlington National Cemetery, October 12, 2021. https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Blog/Post/11413/From-Manila-Bay-to-Philadelphia-The-Life-and-Service-of-USS-Olympia.

Michelle Kukan is a spring 2023 student of Discovering Digital History at Ramapo College. She is a sophomore studying history, American studies and museum & exhibition studies. She is a volunteer for Mahwah Museum’s Veterans Project and works on the Jane Addams Paper Project.