Overview

Post-WWI Italy and the Creation of Fascism

In the 1920s, Italy was still a new country, especially going by European standards. The various regions in the country all having different cultures, economies, dialects, and politics. Some of the biggest differences were between northern and southern Italy. The industrial north was home to many wealthy, educated people, while the agricultural south was home to many uneducated peasants, with about 80% of the southern population being illiterate1Charles F. Delzell, “Remembering Mussolini,” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 12, no. 2 (1988): 119, accessed March 2, 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40257305.. These differences caused the country to be very disunited. Italy suffered from economic problems after the war since hundreds of thousands of returning soldiers were now unemployed. People were becoming fed up with the ineffective Italian government. Some felt a similar revolution to the one in Russia needed to happen in Italy. More than ever, the country needed a strong, unifying figurehead. One returning soldier would soon believe that he was the man for the job.

Benito Mussolini was an editor for the Socialist Party newspaper before the war. The Socialist Party expelled Mussolini for him supporting Italian entrance into World War One2Delzell, “Remembering Mussolini”, 121.. Mussolini was then drafted into the army. During the war, Mussolini became more nationalistic and moved away from socialism. After the war, on March 23, 1919, Mussolini founded the fascist movement, with most of its original members comprising of war veterans. The movement was nationalistic, anti-liberal, and anti-communist. As to what the movement actually wanted, that would change often. He at first called for a republic with universal suffrage, then he endorsed the monarchy and the church and did not want elections, before finally settling on dictatorship3Delzell, “Remembering Mussolini”, 122.. In the end, he did not seem to care what the movement was, as long he could get more people to follow him. And get more people to follow him he did, with Mussolini gaining 10s of thousands of supporters by 1922.

The March on Rome (and Other Cities)

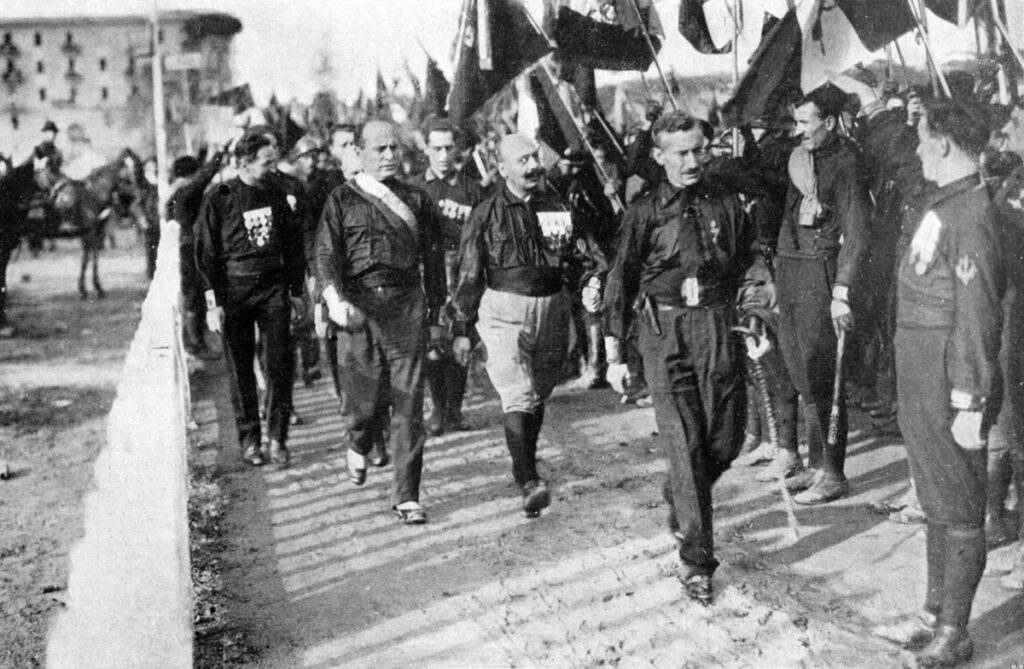

Mussolini and his supporters soon schemed a way to seize power. On the night of October 27-28, 1922, thousands of Mussolini’s “black shirts”, the fascist militia, would descend upon many Italian cities. The plan was to seize post offices, telegraph offices, railway stations, police stations, and government buildings. This would cripple the weak Italian government and ensure they could not mobilize and effective response to the main event: Rome itself. In Rome, the black shirts would confront the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III. They would demand that he make Mussolini the prime minister of Italy. The current prime minister, Luigi Facta, knew that the fascists were planning a coup. Despite this did not believe that it was a serious threat 4Delzell, “Remembering Mussolini”, 124..

The black shirts were ready for a fight, with some of them armed with rifles and hand grenades5Giulia Albanese, The March on Rome: Violence and the Rise of Italian Fascism (United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2019).. They however did not find much of a fight, with the black shirts being able to seize cities such as Pisa, Florence, Venice, Rovigo, and Bologna, and many more, without a fight. Only in the city of Cremona did law enforcement put up any sort of resistance. This fighting resulted in the deaths of four black shirts and seven police officers before the fascists were able to seize the city6Albanese, The March on Rome.. In a few hours, Mussolini supporter’s had taken over most of the infrastructure and communication in Italy. Now they had their eyes set on Rome, with the first black shirts moving on the city in the early hours of October 28.

Once the Italian government had learned of what had transpired, Facta and the loyal generals had to scramble to come up with a way to protect Rome and the King. They wanted to declare a state of siege (the equivalent of martial law in the United States), and succeeded in doing so. However, the King would refuse to sign it, and would have it revoked7Albanese, The March on Rome.. It is not completely known why the King made this decision. The only explanations from him that exist are statements that he made in 1945 after the death of Mussolini and the end of World War Two. These are unreliable as he made them in retrospective to serve a propaganda purpose8Adrian Lyttelton, The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy, 1919-1929 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 91.. There is evidence to suggest that the ineffectiveness of the Italian parliament upset the King, but even then that would not be enough for him to give the country to Mussolini with no resistance. The most likely theory is that the King had heard the reports of violence that had occurred in other cities, and was fearful that if he allowed the state of siege it would cause a civil war. It is also likely that the King doubted the loyalty of the army. Many fascists were ex-soldiers and there were plenty of fascists sympathies in the army9Lyttelton, The Siezure of Power, 92.[.mfn]. No matter what the reason was, in the end the King’s decision ended any sort of government resistance against the fascists. It was then when thousands of black shirts descended on Rome, marching through the streets, without any resistance. The scene was described as such:

What we saw in Rome, then, was a parade of youths sure of the garlands and kisses given to heroes, without any fear of having to fight for them… from noon to dusk the parade was marching across Rome, cutting our line of communications with the theatres. Some of the black-shirted marchers, exhibiting ugly but primitive weapons at their waist, looked capable of administering bodily harm. Yet most were gay, smiling, cockawhoop lads, whom chieftains on bicycles, horseback, or in small cars, tried to marshal into order.

On October 29, the King gave in to the demands of the black shirts. He sent a telegraph to Mussolini, which asked him to come to Rome to become the prime minister. Boarding a train to Rome from Milan, Mussolini insisted that the train needed depart exactly on time, remarking that now with him in charge, everything must run perfectly, which is what created the myth that Mussolini made the trains run on time9Delzell, “Remembering Mussolini, 124.. Mussolini would then become the youngest Prime Minister in Italy’s history.

C.J.S. Sprigge, “WHEN MUSSOLINI LED THE MARCH ON ROME: The Dramatic Scene of Fifteen Years Ago is Described by an Eye-Witness of the Event,” New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 31, 1937. http://library.ramapo.edu:2048/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.library2.ramapo.edu:2443/historical-newspapers/when-mussolini-led-march-on-rome/docview/102144926/se-2?accountid=13420.

Italy itself received the March on Rome rather well . Many were glad that their was some form of strong and stable leadership in Italy, after years of weak government. Even in the government itself, many were not too bothered by Mussolini. Many government officials underestimated him and believed they could influence him with ease10Delzell, “Remembering Mussolini, 125.. The entire world felt Mussolini’s coup, and was likewise received rather well. Countries like Britain and the United States would rather have seen fascist coups happen over communist revolutions. The success of the March on Rome would then inspire other people to try similar coups in other countries, including Hitler in Germany.

Significance

This event, like many things in the 1920s, was a product of the First World War. Specifically, how countries were unable to recover from the war which led to people resenting their governments. In Italy’s case, even though it was a supposed “victor” of the war, the economic and political problems the country had before the war only became worse after the war. The core of the black shirts were made up of disgruntled World War I veterans who felt that their government had done them a disservice. This was a sentiment felt in many countries, especially in Europe. The March on Rome would end up inspiring many across the continent. Mussolini went from a figure known only in Italy to becoming known worldwide in only three days.

The build up to World War Two happened the second that World War One ended, and the March on Rome demonstrates this. Not even four years after the end of the war, the government of a major European power was toppled, with a new ideology taking over. Fascism would soon spread and take root in other European countries. The success of the March on Rome would directly inspire Hitler to undertake the Beer Hall Putsch. These fascist leaders would all have their own ambitions and the result would be Europe once again plunged into conflict.

Citations

Bibliography

- Albanese, Giulia. The March on Rome: Violence and the Rise of Italian Fascism. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2019.

- Lyttelton, Adrian. The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy, 1919-1929. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Delzell, Charles F. “Remembering Mussolini.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 12, no. 2 (1988): 118-35. accessed March 2, 2021, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40257305

- Sprigge, C.J.S. “WHEN MUSSOLINI LED THE MARCH ON ROME: The Dramatic Scene of Fifteen Years Ago is Described by an Eye-Witness of the Event.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Oct 31, 1937. http://library.ramapo.edu:2048/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.library2.ramapo.edu:2443/historical-newspapers/when-mussolini-led-march-on-rome/docview/102144926/se-2?accountid=13420.

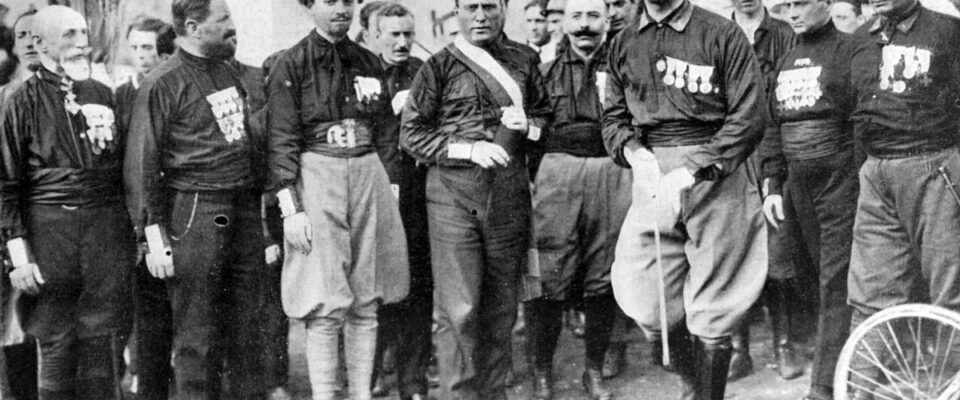

- Featured Image: Quadriumviri e Mussolini a napoli. Illustrazione Itlaiana, October 24, 1922. Accessed March 2, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quadriumviri_e_mussolini_a_napoli.JPG.

Nicholas Buonocore is a student at Ramapo College who toke the Discovering Digital History course in the Spring 2021 semester. He was a junior at Ramapo studying history while taking this course.