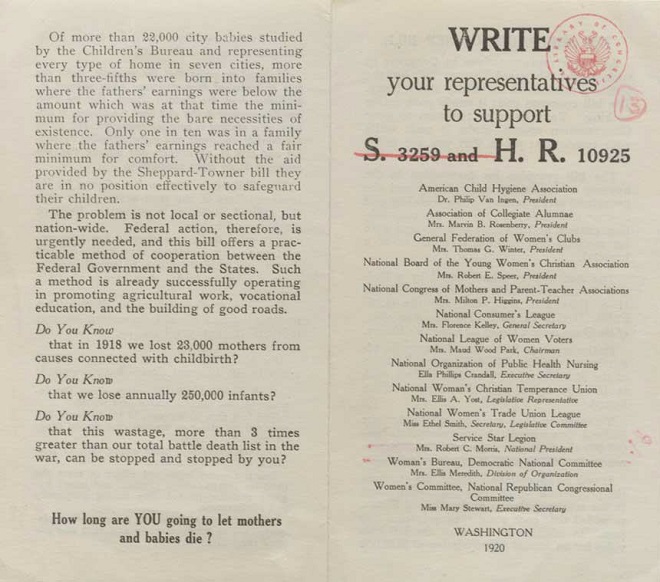

The Sheppard-Towner Act, also known as the National Maternity and Infancy Protection Act, was a Progressive Era reform that attempted to lessen infant and maternal mortality rates. Signed into law on November 23, 1921 by President Warren G. Harding, the act established funds allowing states to create educational programs and literature about prenatal and infant care. Approximately 3,000 prenatal care clinics, 180,000 infant care seminars, and over three million home visits by traveling nurses1 occurred because of the act.

The US Children’s Bureau played a large part in bringing the Sheppard-Towner Act to fruition. Started in 1912, the Children’s Bureau’s mission “was to investigate and report ‘upon all matters pertaining to the welfare of children and child life among all classes of our people.’”2 This and the Sheppard-Towner Act both came as part of the larger rise in progressivism and female empowerment in the 1910s and ‘20s.

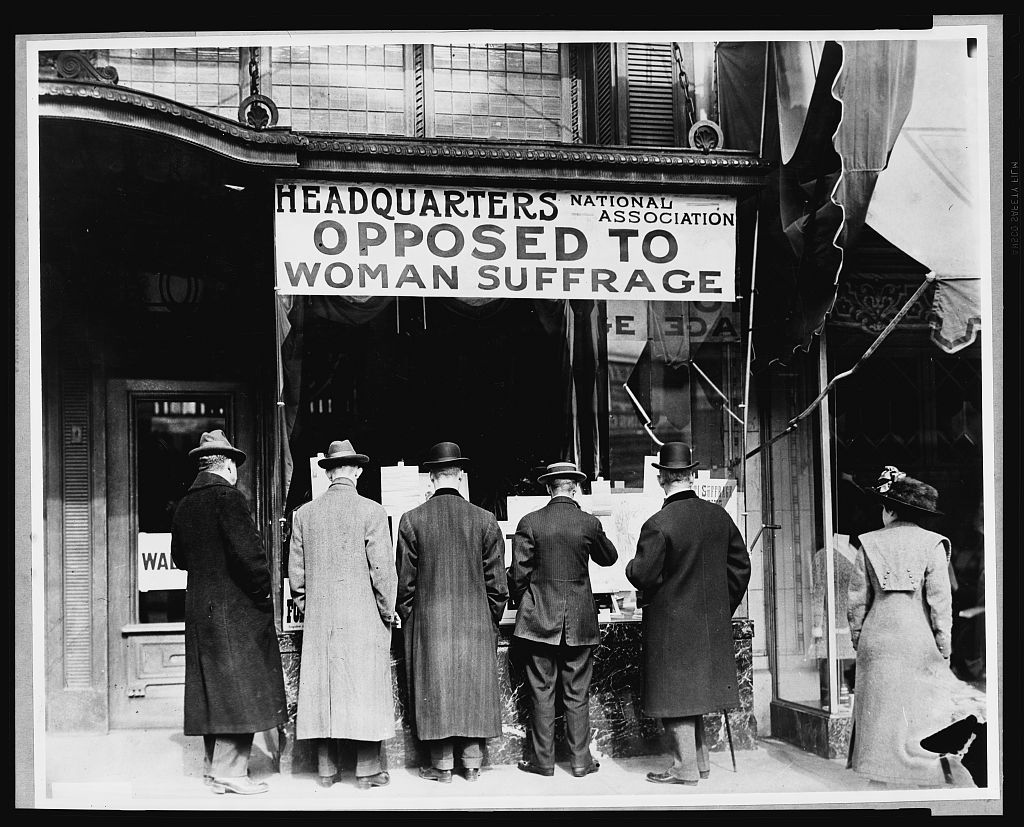

The women’s suffrage movement scored a major success at the tail end of the 1910s when the 19th Amendment passed in 1919, granting women the right to vote. Female activists’ enthusiasm continued into the 1920s, further contributing to the changing idea of women and their place in society. Lynn Dumenil notes in “The New Woman” chapter of The Modern Temper that the shifting ideas of women started as early as the 1890s with women increasingly attending college, entering the workforce, adopting less conservative clothing styles, and becoming involved in politics.3

With women freshly having the right to vote, Dumenil mentioned that male politicians in the 1920s often tried to appease the new group of voters by giving in to their requests. She says as an example, “The Democratic National Convention of 1920 incorporated twelve of twenty recommendations of the newly founded League of Women Voters; the Republican Party adopted five.”4 With the Sheppard-Towner Act passing only two years after women gained voting rights, it is possible that its passage could be attributed to this same phenomenon.

However, the 1920s were also marked by the fading progressive spirit as the decade progressed. While the Sheppard-Towner Act was an early achievement, the funding lasted five years until 1927 when Congress had to vote on a bill that decided whether to renew it. This led to a two-year extension in funding, but Congress eventually decided in 1929 to allow the act to expire. Some of this can be attributed to “increasing pressure from the American Medical Association and a number of conservative senators.”5

This directly correlates with the general feeling about social reform later in the decade. Dumenil expressed how public opinion had changed when she wrote, “Resentment of federal power… was a widespread sentiment that politicians and business interests, eager to keep private enterprise unfettered, manipulated to oppose specific reform legislation.”6 She cited specifically that the impact of the Red Scare allowed welfare programs, including the Sheppard-Towner Act, to be framed as socialism.

This also showcases the conflict between federal and state power during the decade. Dumenil mentioned in the “Public and Private Power” chapter how antistatism increased during the 1920s. This led to many federal acts and programs receiving criticism out of fear of the federal government gaining too much power,7 causing a similar effect where many of these bills faced resistance and deliberate manipulation in some cases.

Therefore, while the progressive attitudes and achievements of and for women in the early 1920s, such as the Sheppard-Towner Act, display changing attitudes and ideas about women in society, the failed renewal shows how the older oppressive ideals returned later in the decade. Fitting the Sheppard-Towner Act into the larger historical context of the rise and fall of progressivism and reform movements shed light on how and why the act came to be and later failed. Without the context, the act’s expiration seems like an unfortunate but isolated event, but learning about the shifting beliefs and the resistance the act faced during the decade illuminates how much more was at play. The Sheppard-Towner Act’s expiration shows that while impactful, the act was one small part of a much larger series of events and social disagreements during the 1920s.

- Madgett, Katherine, “Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act (1921),” May 18, 2017, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/sheppard-towner-maternity-and-infancy-protection-act-1921. ↩︎

- “The Children’s Bureau.” Social Security, accessed February 2024, https://www.ssa.gov/history/childb1.html. ↩︎

- Dumenil, Lynn, The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 60. ↩︎

- Dumenil, 61. ↩︎

- Madgett, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/sheppard-towner-maternity-and-infancy-protection-act-1921. ↩︎

- Dumenil, 66. ↩︎

- Dumenil, 18. ↩︎

Rebecca Gathercole is a senior Communications Arts major with a minor in Creative Writing.