Overview:

Nobody knew it at the time but, nine days in 1926 would change the course of UK Labor History forever. These nine days in 1926 were anything but normal for the people and the government of the UK. During these nine days in 1926 from May 4 to May 12 all workers who were a part of the Trades Union which included almost every worker in the UK, walked off their jobs and the country was forced to a standstill. This monumental event did not occur in a vacuum though. The 1920s in general was not just a time where people partied their hearts and dressed frivolously. As the world emerged from the aftermath of World War I, the 1920s saw a surge of industrial activism and heightened class tensions, where the forces of big business and government clashed with the forces of unions and labor activists. All of these battles throughout the 20s culminated in the 1926 UK General Strike where labor would make its last stand. This blog will summarize the events leading up to the strike, the strike, and its aftermath and put into context with the rest of the events of the 1920s.

Lead up to the Strike:

As with many of the problems that occurred during the 1920s the problems that led up to the General Strike started with the end of World War I. After the end of WWI Britain, like many other European countries, suffered an economic decline. British exports were falling and the economy was feeling. One of the industries hit especially hard during the 1920s economic downturn was coal since exports were down due to effectively free coal from Germany going to France and Italy. To offset the lost profits from the decrease in exports in 1921 the Coal Barons decided to do the easiest cost cutting action a company could do, cut workers wages. In response the miners went on strike, but the Coal Barons still forced them into accepting the lower wages.1

The 1921 coal miners strike wouldn’t be the only Union loss in 1920 that eventually led up to the frustration Union had with the government by 1926. It was all part of the larger theme of the 20s of decreasing union power. Companies in the 1920s were extra vigilant of unions and unionization and had governments on their side helping them along the way to curb their power through the law. Some companies would even use force to stop workers from striking.2 By April 1925 when Churchill decided to put Britain back on the Gold standard and start the events immediately leading up to the strike there had been many failed strikes by many different labor organizations. This made British exports more expensive and forced companies to decrease their prices to remain competitive on the global market. This hit the already low export coal industry especially hard and on June 30th the Coal Barons decided the best way to compensate for this was to enact wage cuts effective as of August 1st. The miners refused to accept this and threatened to strike again.3

The miners realized that last time they failed on their own so this time they enlist the help of the Trade Union Congress, the umbrella organization which all Unions in the UK fall under. They agreed on the 30th of July to put an embargo on movement of coal in the event of a strike. The government freaks out and agrees to give the miners a 9 month subsidy while they figure things out with the Coal Barons.4 The government was unprepared for such a collaboration and knew that it would only make current economic woes worse if such a strike were to happen. This 9 month period not only allowed the government to come up with a new proposal for the miners, but it also gave them time to stockpile in case the miners don’t like the new proposal. 8 months pass by and the government finally comes up with a new plan in March but neither side agrees to accept it. The Barons thought the plan included too little wage cuts and the miners didn’t want any cuts.5 There was no time for the government to come up with a new plan that both sides would like. There was no doubt anymore that the miners were going on strike. The miners wouldn’t be alone though and the events that would unfold over the next year would shape UK labor history for decades to come.

What Happened?:

On May 3, 1926 the UK Trades Union Congress decided that an embargo wouldn’t be enough to force the government and the barons’ hands. They went with the nuclear option and decided to call a General Strike. Over two and a half million workers across almost all sectors of the UK economy would walk off their jobs in show of solidarity with the miners and unified resistance against oppressive labor practices. The strike, which lasted from May 3rd to May 12th, would paralyze key industries, including coal mining, transportation, printing, and shipping, bringing the nation to a standstill.6 This meant no trams, trains, buses or ships. This also meant food and supplies wouldn’t be able to be delivered across the UK. The Trade Unions hoped that the threat of the UK economy crashing down due to a General Strike would force the government and the coal barons to offer a more fair deal which didn’t cut coal miners wages and worsen their working conditions.

The government led by Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin was keen on finding ways for Britain to hold on while the strike was going on. The part of this plan started on the night of May 2nd when the government called for volunteers to help run essential services while the strike was happening. The government was able to secure over 400,00 volunteers to help keep the country running. The government also got directly involved in the distribution of supplies by doing things like taking over the entire milk supply of London, putting the Board of Trade directly in charge of all food distribution, and disturbing food and supplies with armed convoys.7 Although the General Strike was a big hit to the UK economy the government successfully found ways to go around the strike and avoid the worst effects. This is partially why as the strike went on the government’s negotiating position got better while the Trade Union’s position worsened, the opposite effect of a strike.

.

Reactions to the Strike:

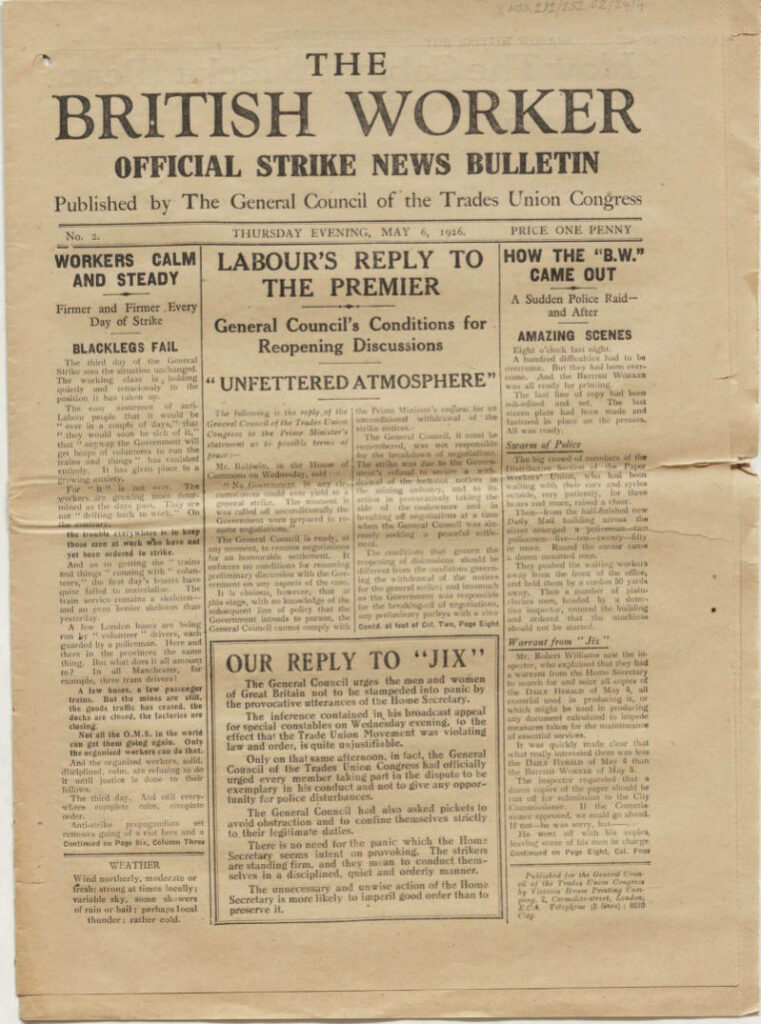

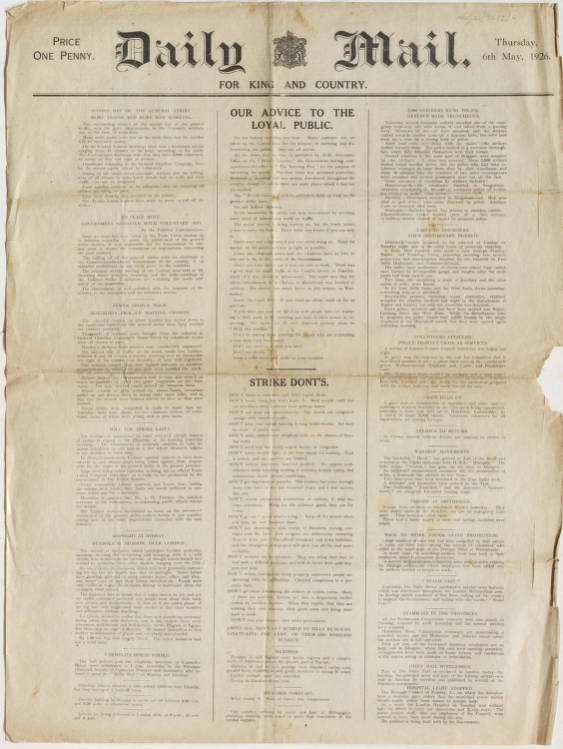

Leading up to the strike and during the strike there was a newspaper war between the Trade Unions and the Cooperations. By the 1920s the era of small local mom and pop newspapers was over, it was now the era of media empires and syndication. Newspapers were becoming full of ads and syndicated stories.8 During the strike though the Newspapers themselves became vehicles of advertisement for each side of the strike and not just for companies. Each side had an entire media empire on its side. There were newspapers like the British Gazette and The British Worker which were owned by the UK Government and the Trade Unions Congress respectively. Then there was the Daily Mail and Daily Mirror which were owned by a giant newspaper corporation that went up against pro-labor newspapers like The Daily Herald.

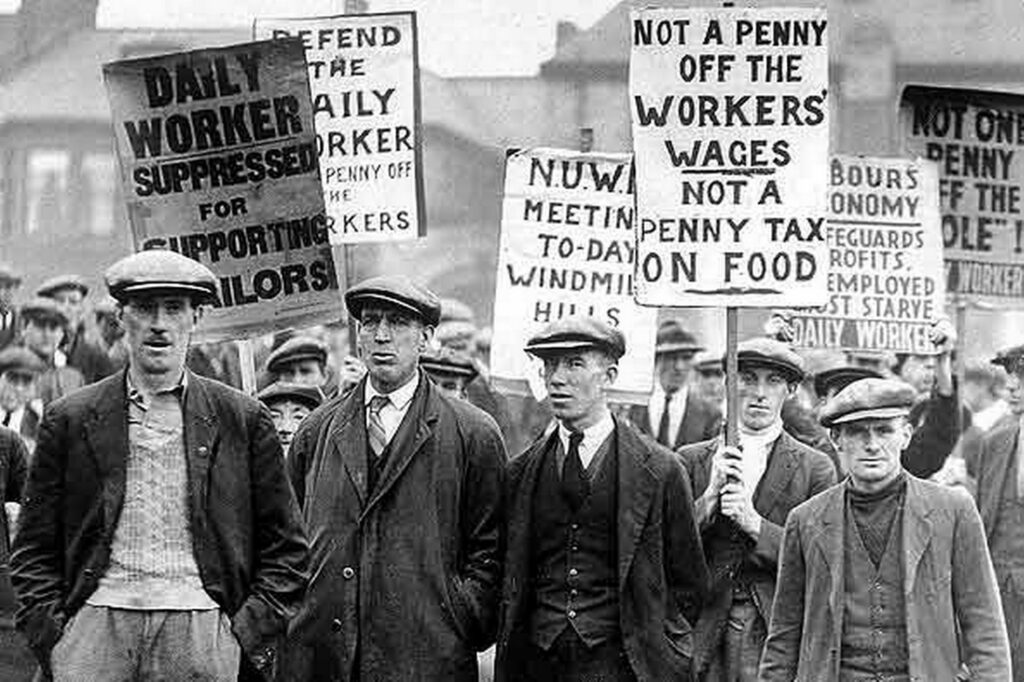

Newspapers on both sides reported the events so differently one might think that they’re reporting on two different events. For example, on the third day of the strike, May 6, 1926, The Daily Mail reported on a story about how 5,000 strikers rushed police officers and caused a lot of disorder.9 While on that same day The British Worker reports on a story about how strikers were swarmed by police outside of the new Daily Mail building.10 Both these events happened yet they frame the strike in two very different ways. One frames them as an out of control mob and the other frames them as an organized peaceful movement that the government is using violent means to suppress. At the end of the day though the government and the corporations had much more established newspapers and were able to win over the public through the use of fear mongering like the Daily Mail did. The radio too became a popular medium for news in the 1920s and the British Broadcasting Company controlled by the government dominated the space and used to decry the workers actions.

Communism, The Red Scare, and the General Strike:

.

The Red Scare, the public’s fear of Communism thanks to the Revolution in Russia, was one way in which the government used its domination of the media to get the public on their side. The Red Scare had made people think twice about joining unions and forced the already existing unions to tread carefully in the policies that they support.11 Even before the strike in 1924 the government started seeding the thoughts of Communism’s involvement when they started purging communists from the Labor Party.12

Workers Demonstrating in the street on May 10th during the strike (Topical Press Agency Getty Images)

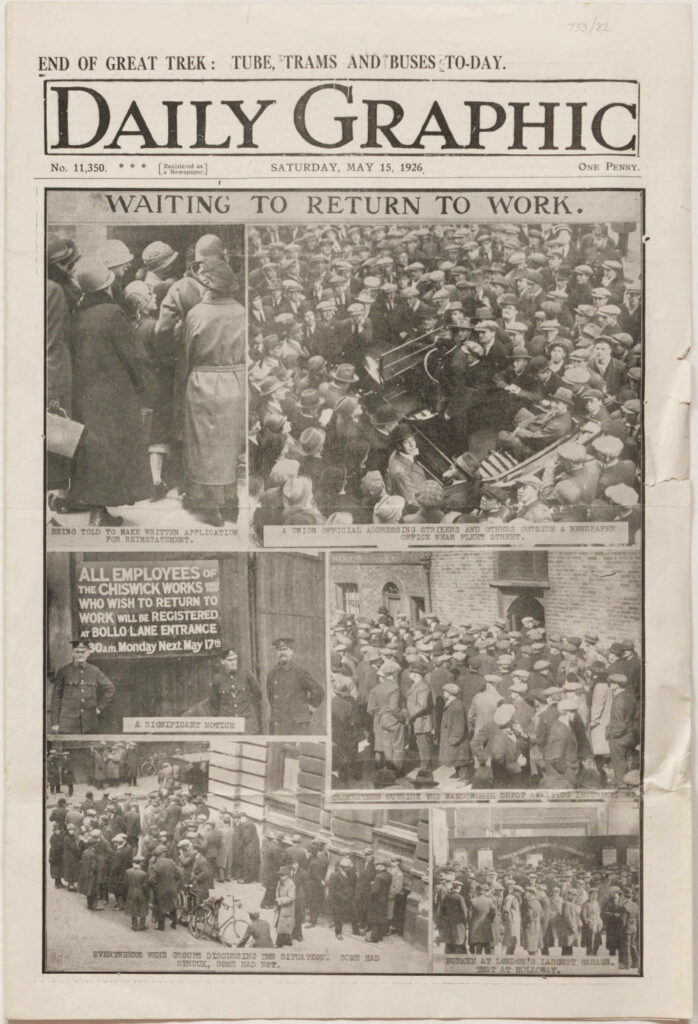

The Outcome of the General Strike:

Ultimately, the UK General Strike of 1926 ended without achieving its immediate objectives. The government outplayed the Trades Union Congress forcing them to call off the strike after only nine days, conceding to the government’s demands for a return to work without a resolution to the miners’ grievances. The UK General Strike would end up in the long list of labor failures and big business victories of the 1920s.

Already at the beginning of the strike things were looking the best for the Trades Union when hundreds of thousands of volunteers showed up to keep the economy running and the government fully utilized its media empire to continually bash the strikers. The death blow to the strike was dealt on May 11th when a judge ruled that only the miners strike was legal while the General sympathy strike was illegal. This ruling meant that strikers could potentially be arrested and that the Trades Union could no longer pay its members who were striking instead of working. That same day the Trades Union Congress voted to end the strike.13 If TUC couldn’t pay its members and its members weren’t legally allowed then there was nothing they could do. Continuing the strike past this point would pit its members against each other and worsen their public appearance. If the TUC continued on it would basically amount to Revolution and not many were willing to go that far.

9 days of striking had achieved absolutely nothing for labor. Everyone would have to go back to work without any improvements and a weaker collective bargaining position. Even the miners had to go back to work and accept the wage cuts after fighting on alone for another seven months.14 The strike did, though , end up costing the government 433,000 pounds (around 40 million of 2024 dollars), the country 30 million pounds (around 288 million of 2024 dollars), and as a bonus 400 thousand more people were unemployed after the strike.15 Now it’s hard to say whether that last statistic is directly because of the strike, but at the end of the day more people were unemployed after the strike than before it. The strike did successfully force the government to spend money on its people like it should in an economic crisis. It’s just that they spent it fighting them instead of helping them.

Aftermath and Legacy of the Strike:

In the aftermath of the strike, the government was not very forgiving to the striking workers. To show this and prevent another General Strike from happening again Parliament approved The Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act of 1927, imposing severe restrictions on unions. The bill made intimidation against picketing legal, put restrictions on union funding for the Labor Party, restricted Civil Service Unions, and most importantly it effectively made any sort of general strike officially illegal.16 Not only did the government want to make sure May 1926 never happened again in UK history, but they wanted to punish the unions for what they did. All the Trade Union Congress and its member workers could do was watch as the institutions they fought so hard to build crumbled before their eyes in only a year.17

The failure of the General Strike dealt a blow to the morale of the labor movement, exposing the limitations of collective action in the face of big business and conservative governments. After the strike, the Trades Union lost half a million members and 4 million pounds in funds in a year. The TUC had felt first the effects of increased corporate power on labor and realized they were no longer a match for them. The 1926 General Strike had been the last great fire to burn in a sea of labor flames that were all but extinguished by 1926. But just as soon as that flame ignited it was extinguished like the rest of the flames. It would another couple decades before that flame could reignite once again in a different group of miners. The 1920s weren’t meant to be the decades of the Union and the Worker. That decade had passed with the Progressive Era. The 1920s was instead the decade of big business and exploitation and the defeat of the General Strike had cemented that. It would take decades for labor to recover from the consequences of the General Strike.

Timeline of the Events Leading Up to, During, and After the Strike

Significance :

The 1926 UK General Strike shines a light on the things that were going on behind the scenes in the 20s. While in America there was no general strike on the scale of the 1926 one in the UK, labor was still being crushed by big businesses and the government. The people who benefited from the 1920s are focused on too much when studying the 1920s. Kids grow up thinking the 20s was a time full of glitz and glamor when it was anything but that. The 20s was really more of Gilded Age 2.0 than a Golden Age. Everything looks fine on the surface but once you go deeper you realize everything is wrong and we’re just ignoring all those problems. The British ignored the problem of the coal miners for 5 years and even though they didn’t have to capitulate to them it still cost the government and the economy millions of dollars. To add on top of the ignoring of American problems there is an even greater ignorance of American then and now of problems going on in Europe at the time. Europe is going through enormous economic hardship and war throughout the 20s while the United States decided to sit and do nothing. FDR was right that when your neighbor’s house is burning down you can’t sit there and do nothing, you have to help and the United States failed to do that. The United States failed to help its struggling citizens and failed to help a struggling world when it’s unique post-war position allowed it to do both.

- Jame E. Cronin, Industrial Conflict in Modern Britain, (London, UK, Croom Helm Ltd, 1979), 52 & 127.

↩︎ - Lynn, Dumenil, Modern Temper, (New York: Hill and Wan, 1995),66-67

↩︎ - Melvin C, Shefftz “The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act of 1927: The Aftermath of the General Strike.” The Review of Politics 29, no. 3 (1967): http://www.jstor.org/stable/1405763.

↩︎ - James Klugman, “Marxism, Reformism, and the General Strike” in The General Strike 1926, ed. Jeffery Skelley, (London, UK: Lawrence and Wishart, 1976), 59-60.

↩︎ - Shefftz, “Trade Disputes”,http://www.jstor.org/stable/1405763. ↩︎

- Shefftz, “Trade Disputes”, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1405763. ↩︎

- D. H. Robertson. “A Narrative of the General Strike of 1926.” The Economic Journal 36, no. 143 (1926): 375–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/2959789. ↩︎

- Dumenil, Modern Temper, 72-73. ↩︎

- “5,000 Strikers Rush Police Defence With Truncheons” , Daily Mail (London, UK), 6 May, 1926, https://cdm21047.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/strike/id/81/rec/2

↩︎ - “A Sudden Police Raid”, The British Worker, (London, UK), 6 May, 1926, https://cdm21047.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/strike/id/9/rec/3

↩︎ - Dumenil, Modern Temper, 63 ↩︎

- John Foster, “Imperialism and The Labor Aristocracy”, in The General Strike 1926, ed. Jeffery Skelley, (London, UK, Lawrence and Wishart, 1976), 40.

↩︎ - Robertson. “A Narrative”, https://doi.org/10.2307/2959789. ↩︎

- Shefftz, “Trade Disputes”, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1405763, 381 ↩︎

- Robertson. “A Narrative”, https://doi.org/10.2307/2959789. ↩︎

- Shefftz, “Trade Disputes”, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1405763 ↩︎

- Robertson. “A Narrative”, https://doi.org/10.2307/2959789. ↩︎

Bibliography

“5,000 Strikers Rush Police Defence With Truncheons”. Daily Mail. London, UK: 6 May, 1926, https://cdm21047.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/strike/id/81/rec/2.

“A Sudden Police Raid”. The British Worker, London, UK: 6 May, 1926. https://cdm21047.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/strike/id/9/rec/3.

Cronin, James, E., Industrial Conflict in Modern Britain, London, UK: Croom Helm Ltd, 1979.

Dumenil,Lynn. Modern Temper, Lynn. New York: Hill and Wan. 1995.

Foster, John,“Imperialism and The Labor Aristocracy”, In The General Strike 1926, edited by Jeffery Skelley, London, UK: Lawrence and Wishart. 1976.

Klugman, James “Marxism, Reformism, and the General Strike” In The General Strike 1926, edited by Jeffery Skelley. London, UK: Lawrence and Wishart. 1976.

Robertson, D.H. “A Narrative of the General Strike of 1926.” The Economic Journal 36, no. 143. 1926: https://doi.org/10.2307/2959789. 375-93.

Melvin C, Shefftz “The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act of 1927: The Aftermath of the General Strike.” The Review of Politics 29, no. 3. 1967: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1405763. 387-406

More Resources

https://cdm21047.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/strike

https://libcom.org/article/1926-british-general-strike